Opinion: What Russia can do with Assad

Two scenarios for early elections in Syria

Since September 30, Russia has been conducting airstrikes against targets inside Syria. Moscow insists that its attacks are against ISIL strongholds, though Western governments and independent groups argue that Russian warplanes are in fact bombing rebel groups engaged in fighting against Syrian troops loyal to President Bashar al-Assad. On October 20, Assad secretly visited Moscow (his first known trip abroad since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011), where he allegedly discussed holding snap elections in Syria. In an editorial for the newspaper Vedomosti, Pavel Aptekar summarizes the Kremlin's options going forward with Assad, whom the West says cannot be a part of Syria's postwar government. Meduza translates that text here.

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's willingness to hold early presidential elections is clearly the result of talks with Moscow. He made this announcement in Damascus before a delegation of Russian lawmakers, just three days after his own visit to Moscow, where he met with Vladimir Putin. According to Bloomberg, citing an anonymous senior official in Moscow, the Kremlin is insisting on early elections.

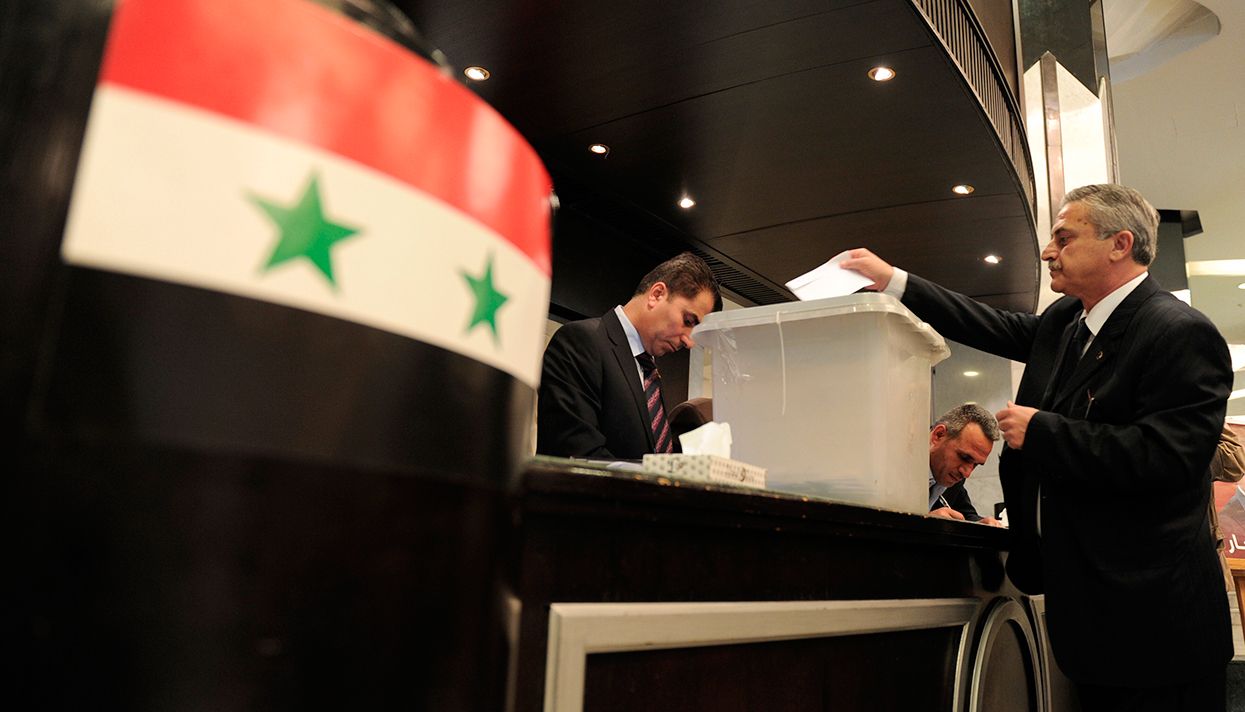

Snap elections by themselves are a familiar, time-tested means of reappointing officials in Russia (especially governors). With Assad, there are two, almost contrary options. The first would be simply "renewing" his popular mandate, which Moscow defends as legitimate, despite the West's objections. Yes, holding early elections in a country beset by civil war, and then declaring the winner a legitimate leader, is theoretically possible, but the value of such an undertaking would be zero.

Any legitimate elections in Syria are possible only after a ceasefire, and a ceasefire is only possible after Russia has defeated ISIL or eliminated most of Syria's armed militants. And it's clear that victory over ISIL, even with the support of Russian warplanes and Iranian forces, won't come overnight. If Moscow sanctions Assad's participation in new elections, it would mean that the Kremlin had rejected past agreements to create a transitional government in Syria, not wishing to lose "its man" in the Middle East, says Alexey Malashenko from the Carnegie Center. If this happens, the Syrian opposition, followed by the West, Turkey, and the Arab countries, would refuse to recognize the election results, and the war would continue.

The Kremlin's attempts to reconcile Damascus and Syria's moderate opposition have been insufficient and contradictory. Many in the moderate opposition are not ready to cooperate with Moscow and Assad, and Russia still hasn't responded to the Free Syrian Army's proposal to hold talks in Cairo.

On the other hand, snap elections could be part of the scenario for Assad's quiet exit. In this case, Assad would decline at the last minute to run for reelection, instead putting forward another candidate acceptable to the moderate opposition, according to international affairs expert Vladimir Frolov.

In this scenario, however, Moscow faces other challenges. The Kremlin was late to establish contacts with Syria's moderate opposition, and it will be difficult for Russia to ensure the safety of the country's Alawite minority. It's also unclear what Moscow can do with Assad's inner circle, whom the opposition accuses of warcrimes and crimes against humanity.

Moscow's last protégé in a similar (far more peaceful) situation also announced early presidential and parliamentary elections. On February 4, 2014, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych promised snap elections, on February 21 he signed an agreement with the opposition, and the next day he fled Kiev, and was ousted from power by an edict of the Verkhovna Rada.