Russia's Citizen K

How Demyan Kudryavtsev came to own the country's best-respected newspaper

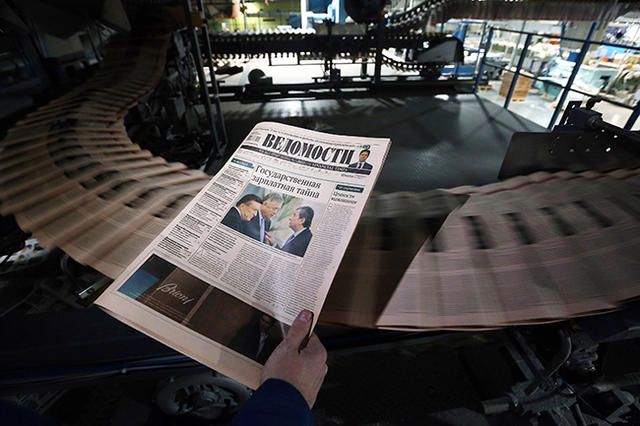

By the end of 2015, Russia’s main business newspaper, Vedomosti, will finally pass to a single owner: Demyan Kudryavtsev. All of the publication’s foreign co-founders—Sanoma Magazines, Financial Time Group, and Dow Jones—have sold him their shares. He has pledged to develop the daily newspaper using his own resources. Kudryavtsev has long been a major player on the Russian media market, though his prominence as a businessman has not been particularly prominent, until lately. For more than ten years, Kudryavtsev was a close associate of oligarch Boris Berezovsky (who died in 2013). Among other work, Kudryavtsev is said to have helped Berezovsky organize support for Ukraine's 2004 “Orange Revolution.” He headed the Kommersant publishing house and ran afoul of Kremlin authorities in the wake of the mass protests of 2011-2012. He managed a return to the media business after three years of being virtually forgotten, equipped with money to buy the country’s main business daily, after, it seems, being “pardoned” by the Kremlin. Meduza special correspondent Ilya Zhegulev tells Kudryavtsev's story.

Emigration

Demyan Kudryavtsev was born in Leningrad. He enrolled in the journalism school at the university, but then decided on an abrupt change in his life course at age 19. He left his parents and joined the growing emigration wave, leaving in 1990 for Israel.

He took Israeli citizenship in place of his former Soviet passport.

Finishing his military service, Kudryavtsev entered the philology department of Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, quickly joining local Russian-language intellectual circles. He self-published the journal Inhabited Island and the online literary journal Eye. Almost immediately upon moving to Israel, he met another Soviet émigré, Anton Nosik, while out walking his dog. They ended up as close friends and even worked together. As one example, they jointly put out the unofficial humor supplement “Vymia” (Russian for “Udder”) for the weekly Israeli-Russian newspaper Vremia.

Kudryavtsev composed poetry that made a name for him first in Israeli, then also in Russian literary circles.

But that was no easy way to make a living, and he had many one-off side projects.

Working on design and computer graphics, for example, Kudryavtsev made an interactive CD-ROM tour of Jerusalem for the city’s 3,000th anniversary.

The most interesting of Kudryavtsev's projects while in emigration was the company Delta III, a startup developing IP telephony. “Demian and his partners thought of it this way: two computers are connected to telephone lines, you call through the telephone line, and the computer can send the signal anywhere, across oceans. There, another computer decrypts the recording and sends it through a local landline telephone. That’s how they suddenly got international phone calls at the price of local ones,” remembers Anton Nosik.

But Kudryavtsev did not wait around long enough for the company to turn a profit. As Nosik recalls, he “needed to have something to eat,” which led him more and more frequently to Russia, where the Internet industry was developing far faster than in Israel.

Head of content

The first legitimately serious business that Kudryavtsev got into was organized by Emelian Zakharov—a former partner of one of the first Russian millionaires, Ilya Medkov.

Medkov started out as a freelancer in the directory and information service Fact—the precursor to the Kommersant publishing house. He made a fortune, became a banker, and was killed in 1993 by a sniper’s bullet. Medkov’s murder had a major influence on his friend Zakharov, who left the country, returning only after two years, when he decided to found an Internet provider. That company would be named Cityline.

In 1995, the necessity of Internet access in every home was not yet a foregone conclusion, and providers themselves were busy generating the first Russian-language online content. This was a task for which Zakharov required manpower. He called his former classmate Nosik in Israel, and Nosik recommended the now-famous designer Artemy Lebedev.

A year earlier, 20-year-old Lebedev had founded the company WebDesign, and along with Kudryavtsev they became some of the first website designers on Russia's newborn Internet.

It was at Lebedev’s that Zakharov first met Kudryavtsev. “He made an incredible impression on me,” Emelian Zakharov now recalls. “He was smart, talented, charming, and friendly, with a sharp and lively mind. The man instantly became my friend.”

It was as one of the five co-founders of Cityline that Kudryavtsev moved to Moscow. At first, before he had found his own place, he shared Zakharov’s apartment. In his role as general producer for the company Netskate (financed by Cityline), Kudriavtsev took part in the creation of the first popular online portals—the daily updated collection at Anecdote.ru or Nosik’s blog, “The Evening Internet.” It was the very beginning of the Russian Internet. “At the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s, there was nobody on the internet that hadn’t either used our consulting services or been our clients,” remembers one of the managers then working with Kudryavtsev.

As Zakharov recalls, Cityline was “unbelievable in its efficiency” as a company. “When we sold it, we had as many clients as our main competitor (Golden Telecom), with a staff of just 40 employees, while Golden Telecom had nearly a thousand.”

From initial investments of $4 million, Cityline sold to the very same Golden Telecom for $29 million after just five years.

At the time of the sale in 2001, Kudryavtsev owned 10 percent of Cityline shares, becoming a dollar millionaire at age 30 after making $2.9 million from the transaction.

While working at Cityline, Kudryavtsev met the man who would become his patron and older comrade over the next ten years.

One of the Cityline co-founders, Georgii Shuppe, was married to Ekaterina Berezovskaia, the younger daughter from the first marriage of oligarch Boris Berezovsky. The latter had a good relationship with his son-in-law. When Shuppe suggested that Berezovsky invest in a project with potential in 1998, he quickly agreed, and became a shareholder in Cityline.

Boris Berezovsky made good friends with the team at Cityline. It was this time when Berezovsky was the executive secretary of the Commonwealth of Independent States, the loose federation of post-Soviet successor states, and was lobbying for the creation of a customs union. He once gathered the company’s top management and asked them to come up with a unified system of communication and accounting for the union to operate on. Diving in eagerly, the young businessmen came up with a solution that remained only to be presented at the meeting of CIS prime ministers. Berezovsky told them: "you came up with it, present it yourself."

Emelian Zakharov refused, while Cityline general director Rafael Filinov had a lisp and shied away from public speaking. Kudriavtsev would have to be convinced. As Filinov retells it, the proposed speaker’s look was the real problem. “He was always all rumpled, dressed like a bum. But my wife was in charge of the shopping mall Nostalgia, with fantastic suits. We took measurements quickly, brought him the suit, only we were off by a bit on the waist of the pants,” Filinov laughs. In the end Kudriavtsev went to the meeting, at least decently dressed but still unshaven. So he had to shave on the go in the bathroom of the President Hotel, where the meeting of prime ministers was being held. Upon seeing Kudriavtsev all cleaned up, Berezovsky froze in astonishment. “Couldn’t you go out like that all the time?” asked the oligarch with the intonation of a schoolteacher.

The success of that presentation, made by then 27-year-old Kudriavtsev, left an excellent impression on Berezovsky. He singled him out amongst the top leadership of Cityline, thereafter giving orders directly to him.

Berezovsky’s man

Kommersant editor-in-chief Andrei Vasilev first met Kudriavtsev in 1999. “He was always wearing something like a black field coat, and was constantly carrying some documents for Boris [Berezovsky],” Vasilev says.

Kudriavtsev surprised him at a meeting for the election campaign of the Edinstvo (“Unity”) movement—a sort of prototype for United Russia (the country's current ruling party). Berezovsky was one of the founders of the movement. Vasilev claims he was required to attend as the general director and editor-in-chief of the Kommersant publishing house that Berezovsky owned.

“Everybody at the meeting had started wondering: where are we going to find somebody to handle the creative side?” Vasilev explains. “Then Demian suddenly gets up and says: there’s this guy Orlusha, hell of a guy, he’ll crank out creative in spades for you. And then everybody looked at me in surprise.”

Vasilev himself was friends with Orlusha (full name Andrei Orlov), who was both a poet and a political analyst. They had worked together briefly, and Vasilev had not expected anybody else to put forward his candidacy. Orlusha was immediately approved for the role, and he was a great asset in the handling of the subsequent electoral campaign.

By 1999, Kudriavtsev was Berezovsky’s right-hand man. He was his personal press secretary and advisor. He had de facto control over Berezovsky’s main media holdings—the TV channel ORT and Kommersant. A partner of both men told Meduza it was Kudriavtsev himself who penned the campaign strategy for Edinstvo, which Berezovsky then passed off as his own.

Beyond that, the same source contends, Kudriavtsev even wrote the first public speeches of Vladimir Putin, before the presidential elections in March 2000.

As is well known, Boris Berezovsky and Vladimir Putin had a serious falling out shortly after the election. Demian Kudriavtsev went on working for the now-disgraced oligarch.

It was Kudriavtsev who set up the 2000 deal to sell ORT to Roman Abramovich. That was when Berezovsky ran into conflict with Putin, and the Presidential Administration decided to take the TV channel under its control. According to a friend of the now-deceased oligarch, “After the betrayal by Kostya [Ernst, general director of ORT], who stopped following Berezovsky’s directives under pressure from Presidential Administration head Aleksandr Voloshin, Boris had nobody left that he trusted. And yet he continued to trust Demian like his own son.”

The stake in ORT was sold for $300 million.

A source close to the deal said that Kudriavtsev took a commission of just under 1 percent.

When Berezovsky left the country in the fall of 2000, going first to France and then to London, Kudriavtsev went along with him.

One day, when Kommersant special correspondent (co-author of a best-selling quasi-autobiographical book on Vladimir Putin, First Person) Natalia Gevorkian was already living in Paris emigration, her telephone rang.

It was Kudriavtsev; they would not let him into Russia and had sent him back to Paris on the same plane he’d arrived on.

“I’m in shorts, he said, one bag and nothing else with me. And no money either,” Gevorkian remembered in conversation with a Meduza correspondent. “He came over to my place, and was not in very good shape. Depression was setting in, and it lasted for quite some time.”

Kudriavtsev had no Russian passport—he had yet to finalize Russian citizenship after the collapse of the USSR.

He traveled on his Israeli passport, getting visas for his time in Russia. It was only in 2005 that he would get a permanent visa, after which he could also apply for citizenship.

Kudriavtsev rented an apartment in London where Berezovsky had settled, bringing his wife and kids to join him.

He continued to manage Berezovsky’s remaining media interests, which still included Nashe Radio, Kommersant, and the television channel TV-6. “He was constantly with Boris,” said businessman Yuli Dubov, a friend of Berezovsky. “Because Demian was such a smart guy, Boris really enjoyed talking with him.”

Kudriavtsev was among the few who dared butt heads with Berezovsky. And one of their main disputes arose out of the situation in Ukraine in 2004.

Point-man for the revolution

In emigration, Berezovsky remained fully engaged in politics: he assured everyone that in would take just a bit more and “the regime in Russia will fall.” And while that had yet to happen, the oligarch took part in political projects in Russia’s neighboring countries.

The idea of supporting Viktor Yushchenko in the 2004 Ukrainian presidential elections was born when David Zhvaniya, a deputy in the Ukrainian parliament, appealed to him for help. Along with another deputy and businessman named Petro Poroshenko, who serves today as Ukraine's president, they promised to reward Berezovsky for his support. According to the businessmen’s plan, Yushchenko was to become the president and Poroshenko the prime minister. Berezovsky agreed, and spent more than $70 million on Yushchenko’s campaign (and the Maidan protests that followed it). Representing his interests in Kiev was none other than Demian Kudriavtsev. In the heat of the standoff on the Maidan, he went around the tent city giving out some sort of orders.

However, Yulia Tymoshenko, a bright star in those events and Ukraine's future prime minister, persuaded Berezovsky to bet on her instead of Poroshenko.

Kudriavtsev had a serious clash with the outcast oligarch over this issue, urging Berezovsky not to get involved in power struggles among people who were, effectively, strangers. He told Berezovsky to stay the course, supporting the Yushchenko-Poroshenko tandem.

In September 2004, not long before the elections, Yushchenko was poisoned, spending a long time in the hospital and falling out of sight. And when he reappeared, he had suffered horrific transformations in appearance. This bothered Berezovsky, and a scheme with Tymoshenko—the most charismatic politician of the moment in Ukraine—seemed more appealing than ever. For that reason Berezovsky told Yushchenko that he would only continue supporting him if he agreed to take Tymoshenko as prime minister in place of Poroshenko.

Ultimately, Berezovsky would pay dearly for trusting Tymoshenko. The oligarch was counting on cashing in for his support in the elections, as he had in Russia after backing Boris Yeltsin in 1996. In Ukraine, he had his eye on the telecoms monopoly Ukrtelekom, the Odessa Port Plant, a stake in the steel mill Krivorozhstal, and a plot for the construction of a million square meters of housing in Kiev. Berezovsky was plainly tricked; he was barred from entering the country, while Tymoshenko and Yushchenko stopped taking his calls.

Yet Berezovsky and Kudriavtsev fared better in another revolution. Not long before his death, Berezovsky told me that along with his partner and friend, Badri Patarkatsishvili, he’d financed a “consulting group” in 2005 that helped Kurmanbek Bakiev become President of Kyrgyzstan. The head of that group was Demian Kudriavtsev.

The “Tulip Revolution” was far cheaper than its “Orange” predecessor—costing Berezovsky a mere $5 million.

The victorious Bakiev compensated Berezovsky with a stake in a gold mining interest—the Jerooy deposit with the second biggest reserves in the country.

The company that took control of the deposit—Global G.O.L.D. Holding Gmbh—was headed by Rafael Filinov, who Berezovsky knew from Cityline, and Kudriavtsev was among the minority shareholders.

After an investment of only $12 million, Filinov later sold the enterprise to a Kazakh company for $130 million. Kudriavtsev got another big payday from the deal—around $3.5 million.

Kommersant

Having finished with the revolutions, Berezovsky decided in 2005 to refocus on bringing to order his main Russian media holding, Kommersant.

Kudriavtsev told him at the time that the impending crisis of the print media was apparent to shareholders, but that editor-in-chief Andrei Vasilev was obstructing needed changes. Berezovsky went for a management shakeup. The publishing house was stagnating, time for new blood, he explained.

Andrei Vasilev and part of the leadership was sent to Kiev in spring 2005 to launch the newspaper Kommersant-Ukraine.

The head editor at Kommersant, as proposed by Kudriavtsev, became a former employee who then headed Gazeta.ru, Vladislav Borodulin. Former NTV-Plus director Vladimir Lensky became the publisher’s general director. Kudriavtsev missed the mark with this latter appointment; the arrogant Lensky immediately had a falling out with the other leaders of the newspaper.

Little acquainted with the working protocol among editors, the new manager made enemies out of the staff with his very first order: a ban on drinking while at work. At the end of 2005, a whole Kommersant delegation flew to London. Their main demand was the dismissal of Lensky, and he was out by the first days of 2006, with Kudriavtsev himself named as the replacement.

Kudriavtsev immediately impressed the staff, recalls Maksim Kovalsky, former editor-in-chief of the magazine Kommersant-Vlast. The new general director stayed out of editorial issues, and was more one of the group than Lensky, who had tried to corporatize Kommersant's homey atmosphere. “I remember when one of the oldest employees, Nikolai Vardul, came up to me, dumbfounded. Supposedly, he goes into Kudriavtsev's office, and he's sitting there in an armchair with his foot tucked under himself. That was a new one!” laughed Vladislav Borodulin.

In 2006, Berezovsky transferred his Kommersant shares to his friend and partner Badri Patarkatsishvili, who began preparing the sale of the business. A source close to discussions of the deal said Berezovsky was planning to sell Kommersant for $120 million. That was a decent price, the source thought, taking into account the publisher’s 2005 profit of $13 million.

But Patarkatsishvili shoved Berezovsky aside in the sale, asking Kudriavtsev to seek potential buyers himself.

Kommersant, Patarkatsishvili reasoned, was not a commercial enterprise, but a political one, and it could be sold for far more.

In the end, Kudriavtsev attracted one of the richest businessmen in Russia, the billionaire owner of Metalloinvest, Alisher Usmanov.

In spite of Usmanov’s later claims that he paid $200 million for Kommersant, a source close to the deal says the real price tag was higher: $280 million. And Kudriavtsev again took his commission, comprising 1 percent of the sale.

After Usmanov acquired the business, the question of the general director’s position arose. Usmanov was not originally committed to keeping Kudriavtsev. Such appointments already required Kremlin approval by then, and the deputy head of the Presidential Administration, Vladislav Surkov, could not forgive Kudriavtsev’s role in the Orange Revolution.

It was Andrei Vasilev, returning from Ukraine, who stood up for Kudriavtsev. He told Usmanov that he’d be more comfortable collaborating with Kudriavtsev than with “some kind of metalworker.” Kudriavtsev also benefitted from the fact that the sale of Kommersant was informally overseen by Dmitry Medvedev, who was then deputy prime minister and a potential successor to Putin in the 2008 presidential election. Vasilev remembers his conversation with Medevedev: “What is it you want with Kommersant? what is it you want out of me?” Vasilev asked. Medvedev, according to the editor-in-chief, responded ironically, “I want Kommersant to be like [it was] under Vasilev.” Then Vasilev complained about Surkov, who “dictates from behind Usmanov who should be named general director.” Medvedev said he’d look into it, and Kudriavtsev remained in his position for the next several years.

Kudriavtsev’s Kommersant became more modern. It spawned its own radio and television stations, and several magazines. The newspaper itself went from black-and-white to color ink. Still further, the website, which had earlier merely duplicated the newspaper (behind a paywall), was separated into an independent resource, making money off advertising.

They changed the layout, began to upload news content updates throughout the day, and opened it up for all readers. As a result, according to then commercial director Pavel Filenkov, in place of the $200,000-300,000 a year that the site had made from selling subscriptions, Kommersant Online began to generate upwards of $5 million annually from ad sales.

In 2008, the government unexpectedly relieved the newspaper Rossiiskaia Gazeta of its monopoly on publishing bankruptcy notices. Kommersant won a competition to reassign the privilege. In 2011 alone, the publisher made $20 million off of its Saturday printing of Arbitration Court proceedings.

Kommersant TV, on the other hand, turned out to be one of Kudriavtsev's bad ideas. Its lack of popularity can be judged by the fact that even in the publisher’s cafeteria, its own channel played for just a month before the television was switched back to the customary favorite, Discovery. The television project was shut down immediately following Kudriavtsev’s departure, by which time, in Filenkov’s estimate, the station had lost $30 million.

Kudriavtsev explained then that the project had been killed during takeoff, that given investment over another couple years, it would have become profitable. The radio station Kommersant FM also operated at a loss, but it wasn't closed down. For comparatively small costs, it helped develop the brand of the entire media company.

Another unsuccessful Kudriavtsev project was the launch of the magazine Citizen K in 2007. The new publication was kicked off to much fanfare: Russian pop star Zemfira sang at the launch party, and everybody who purchased the first edition of the magazine got a free copy of her new album. But in five years, the publication never turned a profit. According to Pavel Filenkov, Citizen K “siphoned off” $7 million from the publisher. The magazine was also shut down immediately after Kudriavtsev’s departure.

“At any rate, thanks to the fact that Kommersant TV was a separate ‘sister’ project without a juridical link to the publishing house, its profit remained around 10 million dollars annually,” says Filenkov. “Although that did not greatly concern the investor. For either Badri or Usmanov, the yearly income of Kommersant amounts to a rounding error on the cost of their breakfast.”

Usmanov was satisfied that his media business was not asking him for money, but something entirely different did concern him.

Enter the Kremlin

At the outset, the paper's editorial policy remained unchanged under Usmanov. “Kommersant remained the same as it had been. Demian was not involved with content,” explains former head editor of Vlast Kovalsky. “At times he just said, 'This could be a topic,' or asked, 'Is this of any interest to the magazine?' I would calmly respond, you know, that I’m not interested, and the conversation ended. Demian never insisted.”

But over time, there were excesses. In November 2007, Kommersant ran an interview with Finansgrupp head Oleg Shvartsman, in which he detailed “velvet reprivatization” and new voluntary-compulsory methods for consolidating private holdings in state hands under the supervision of the influential Igor Sechin. “I had gone to St. Petersburg to open an ice rink, when the calls started coming in. It was a sh**show,” Vasilev remembers. “By evening, Demian called to say, 'Come back immediately on Sunday—they’ve really got me by the balls here!'”

On that occasion, Kommersant's leadership was able to fend off the furious claims of the Presidential Administration. The pressure was ratcheted up gradually, though, especially in the year leading up to the parliamentary elections. In early 2011, Kudriavtsev called Vlast's editor, Maksim Kovalsky, several times to ask that he use more care in writing about the upcoming Sochi Olympics. The reason was that, in multiple conversations with Kudriavtsev, the deputy head of the Presidential Administration, Aleksei Gromov, had supposedly argued that Kommersant-Vlast was violating media principles on the dissemination of objective material. For Kovalsky, the most surprising part was when Kudriavtsev next said, "You know, Gromov isn’t that far off the mark."

“I understood the situation as meaning he was no longer our envoy there, but their agent here,” Kovalsky recalls.

The conflict became even more intense in the fall of 2011, when Kudriavtsev issued an order under which the editor-in-chief of the media group, Azer Mursaliev, could make editorial changes in any of its publications after submission by individual head editors. Kovalsky made it loud and clear that he would never send columns for the editor-in-chief’s approval, and if Mursaliev cared to make changes, he had better take over running the magazine himself.

Finally, in the magazine issue immediately following the Duma elections in 2011, Vlast ran a picture of a defaced voting ballot with profanity directed at then Prime Minister Vladimir Putin scrawled across it. Enraged, Usmanov personally demanded Kovalsky’s dismissal, and Kudriavtsev did not protest. He did then take responsibility for the messy situation himself, however, and also promised to resign. The scandal in the press reached a point where businessman Mikhail Prokhorov offered to buy the publishing house from Usmanov, and Vladimir Putin himself publicly mentioned the defaced ballot.

But it wasn't until June 2012 that Kudriavtsev resigned, when he claimed the move was his own decision, though multiple sources attest that his departure was not voluntary.

The Kovalsky scandal was the last straw for the Kremlin and Usmanov alike, the latter tiring of having to react to angry calls from above about each new edition of the newspaper. Usmanov wavered, but Gromov was insistent: bigger heads than Kovalsky had to roll.

The parties were forced to announce a peaceable end to the relationship. As compensation for his resigntation, Kudriavtsev is said to have received $3 million. The former general director of Kommersant found himself jobless. The Kremlin had effectively blacklisted him, scaring off any potential employers. He was tapped as a candidate for multiple positions, only to be crossed off the short-list at the last minute.

After the departure of Rafael Akopov as general director of Profmedia, for example, rumors circulated that Kudriavtsev would take the position. But billionaire Profmedia owner Vladimir Potanin removed him from the list of candidates. Kudriavtsev was in extremely rough shape: pale and not just thinning but wasting away. He fell seriously ill. “He was barely saved from the afterworld,” says his friend Emelian Zakharov.

So as not to sit idle, Kudriavtsev created the company Yasno–Communications, which carried out consulting in multiple spheres, including development. In one instance, the agency had a project in 2014 to develop the grounds of Moscow State University for the National Intellectual Development foundation, headed by Katerina Tikhonova (rumored to be one of Vladimir Putin's daughters).

The agency did research, archival work, surveys, and was supposed to prepare a framework on that basis.

But suddenly there was no longer a need for Kudriavtsev’s services. According to a source with links to state security agencies, the surname of the Yasno-Communications owner was still enough to bother patrons in the Kremlin.

The buyer

In late 2013, the Finnish company Sanoma Magazines ran a press release indicating in which markets it planned to remain active. Only one country where Sanoma was previously active was left off: Russia. That news piqued the interest of three friends: Vladimir Voronov, Martin Pompadur, and Demian Kudriavtsev.

London-based Voronov was in charge of the News Media Radio Group (the owner of Nashe Radio, Best FM, and Radio Ultra), founded in partnership by Boris Berezovsky and the Australian media magnate Rupert Murdoch.

Martin Pompadur, meanwhile, was chairman of the board of directors at the European subsidiary of Murdoch’s NewsCorp.

The friends decided to buy up Sanoma’s Russian business (all of its media holdings were to be sold in one bundle), including a stake in the company Business News Media, which publishes the newspapers Vedomosti and The Moscow Times. Formally, the joint-stock company belonged to the Cyprus offshore firm Delevoi Standard, Ltd. A third of the shares in this Cypriot company belonged to Finnish Sanoma Magazines, while the other two-thirds were split between Pearson (printer of Financial Times) and Dow Jones (The Wall Street Journal).

Negotiations were tense. Sanoma set its price, and—having done its research—the three partners proposed a steep discount. In fact, the publisher was putting up serious losses each year. Moreover, the ownership agreement was structured such that Sanoma, Pearson, and Dow Jones split annual royalties of $10 million from the business three ways. But whereas the brands Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal ran on the top line of Vedomosti, and the Western editions could benefit from generous content-sharing with the Russian paper, Sanoma got nothing but this royalty.

Drawing attention to the losses benefitted the buyers, who secured the desired discount. Beyond that, politics came into play: the annexation of Crimea and Western sanctions, followed by new legislation banning more than 20-percent foreign ownership of Russian media outlets.

After that law passed, Sanoma representatives appealed directly to Kudriavtsev with an offer just one-third of their original asking price.

Talks with Kudriavtsev were kept under the strictest secrecy. It was only in December 2014 that Pearson and Dow Jones discovered that he was the buyer, and they were very displeased.

Kudriavtsev’s reputation, to their mind, was ambiguous. It was at that same time that the deal became known among the top managers at Vedomosti. The purchase had been completed entirely without their participation—nobody even bothered to ask them.

“We were sold like potatoes, behind our backs,” Vedomosti chief editor Tatiana Lysova fumes. “I told Demian: you bought us, and you didn’t even talk with me. He responded: and what would that have changed? You would have said, apparently, 'Demian, we don’t like you,' and I’m supposed to reconsider as a result?”

In May 2015, Kudriavtsev completed the transaction and placed on the board of directors his friends, Pompadur and Voronov, who were not technically part of the deal, but were its de facto beneficiaries.

It bears noting that, in addition to the stake in Business News Media, Kudriavtsev wanted to buy the company Axel Springer Russia, which prints the influential business monthly Forbes. But he couldn’t reach an agreement—the publisher’s general director, Regina von Flemming, was strongly opposed.

From April through the end of the summer, Pearson and Dow Jones were in search of practically any buyer for their shares, which the law in any event demanded they give up. There was no interest in Vedomosti, however. The partners hired Moscow lawyers to find them some way of staying in the Russian market. They met with Aleksandr Zharov, the head of Roskomnadzor (Russia’s media regulatory watchdog), but he could offer no help to investors. There was no alternative.

In September, literally a month before the final deal went through, the foreign shareholders were approached unexpectedly with an offer from Sergei Petrov, a Duma deputy and the founder of the car dealership chain Rolf. He was interested in Vedomosti. Later, however, he withdrew is offer. Upon hearing that news, Tatiana Lysova contacted him and set up a meeting. “I figured that for a stable future at Vedomosti, an arrangement with two investors independent from one another would be better. In case one of them suddenly wanted to do something unfortunate, there would still be the possibility of appealing to the other,” Lysova explains regarding her intervention in the negotiations. “I also supposed that two significant, independent investors might mean some chance of convincing the foreigners to hold onto at least a small stake in Vedomosti. And Petrov himself gave no cause for suspicion—he is an entirely respectable person of like mind and values to ours. He's hardly likely to do anything to the detriment of our operations.”

Lysova succeeded in changing Petrov’s mind, and he submitted a second offer. But this time the sellers rejected the application: Kudriavtsev was a sure thing, and Petrov hadn't out-bargained his offer.

Petrov's representatives sent a letter asking for more time to carry out due diligence, to check up on the financial standing of the investment. The sellers had no time, though, and in any event another buyer was ready.

Lysova again went to meet with Petrov. Finding out that his people had dropped the ball, the businessman promised to submit yet another offer. The next day, however, Lysova discovered that Petrov had decided against fighting for the shares. This time, the explanation came not from Petrov, but from one of the top managers at Rolf in charge of investment.

“Look at it our way,” he told Lysova nonchalantly over the phone, “it’s a complicated deal with many risks. Sergei is a Duma deputy, the profit prognosis is uncertain, and we are also in the middle of downsizing our main business. Right now, for example, we have decisions to make, like whether or not to open a new dealership. And the costs involved are comparable. Only there we have strong EBITBA [Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization].”

Lysova understood perfectly. “I get it,” she said. “We can’t provide 300 percent EBITDA. We are not a dealership—that’s totally true. We apologize for being unable to compete with the automobile trade.” With that, she hung up.

“Demian said that the money was all his, although we heard that he has places to take out loans,” said one participant in talks from Petrov’s camp. “He [Kudriavtsev] promised, if we raised our offer, he would do the very same. Does Sergei need to be dealing with things like that? He'd also wanted to maintain somehow the presence of Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal in Vedomosti as a shield against risks to its reputation. But that was not possible. On the whole, the minuses outweighed the pluses of the purchase.”

According to an insider source, Petrov wanted to set out to save the free speech, while Western investors were merely interested in selling their shares for the highest price.

By fall, the market was left wondering whether Kudriavtsev spent his own money on Vedomosti, or used someone else's—a shadow investor's—to complete the deal.

The newspaper itself reported its valuation at 10 million euros, including its debt. According to information at Meduza, the newspaper's overall debt was roughly 7 million euros. Those obligations were taken up by Kudriavtsev's friend Pompadur. According to the news agency RBC, the liabilities cost Pompadur some 6 million euros.

So it turns out that a friend chipped in 6 million euros for Kudriavtsev. He also had enough to cover the 4 million euros he paid back in the spring for the stake from Sanoma.

Kudriavtsev's cumulative income over the past 15 years amounts to $20 million, including includes his salary, which averages $1 million annually, first from Berezovsky, and then from Usmanov, as well as commissions and income from the sale of shares in various companies. He's lived rather modestly, without big luxury-item purchases. One of his biggest investments was the construction of a house in Pirogovo on the Ostashkovsky highway. But this year, Kudriavtsev sold that house for $1.5 million.

To complete the deal, it was imperative that Kudriavtsev resolve his biggest issue: the Kremlin's disfavor. It seems as if he succeeded on that front. Back in the spring of 2015, Kudriavtsev said he was discussing the Vedomosti deal with authorities and nobody had blocked him, so far. Perhaps the Kremlin, tied up in several geopolitical conflicts simultaneously, was simply not up for it. Perhaps (and not without reason) the presidency figured it could make arrangements with any owner—so long as he was a Russian citizen, the levers of influence should suffice. Lower ranking officials presumed that somebody must be behind Kudriavtsev.

According to Meduza's sources, Kurdiavtsev told friends that Roskomnadzor told him they would only speak with the real owner, when he needed to update the license registries for The Moscow Times and other former Sanoma publications.

Kudriavtsev also had another problem: he tried renouncing his Israeli citizenship, but Israel has no forms confirming that procedure. Roskomnadzor, meanwhile, was unwilling to accept a copy of the announcement. For that reason, Kudriavtsev had to register Vedomosti and The Moscow Times under his wife’s name.

When Kudriavtsev ended up as the lone buyer for Vedomosti, he informed Tatiana Lysova. At first, she promised to resign, and Kudriavtsev was not about to stop her. But in November, at a meeting with the staff, Kudriavtsev openly announced that he would be happy if Lysova decided to stay. And so she did.

As insurance, however, she requested that investors change the company charter before the deal was completed. The final document clearly laid out that content-decisionmaking is the exclusive province of the head editor. Any changes to the corporate charter are subject to the approval a majority of full-time staff members. Additionally, the chief editor gained a seat on the board of directors of Vedomosti’s parent company.

Lysova has expressed cautious optimism. “To many of us, it seemed that Demian wanted to become general director in order to control all procedures personally. But when he met with the staff, he said without any prompting that he has no interest in that. And he wants the current general director, Gleb Prozorov, to stay on in his position."

According to Lysova, Kudriavtsev handled himself with restraint. In response to the question of whether he intended to change anything, Kudriavtsev said he had no concrete decisions in mind, but would like to learn in more detail what works at Vedomosti and how. Prozorov is truly a member of the old guard, working at the paper since 1999. But the whole team will not be kept intact. The former director and publisher of Vedomosti, Mikhail Dubik, for example, left his position at the beginning of November.

According to Lysova, inasmuch asVedomosti's staff thinks about Kudriavtsev, it thinks he earned getting the newspaper. “Throughout the whole story, absolutely everybody—myself included—showed their weaknesses and were full of doubts. Kudriavtsev alone acted decisively, firmly aware of what he needed and he made a great effort to ensure the deal worked in his favor,” Lysova says.

Kudriavtsev becomes Vedomosti's legally-confirmed owner before New Year's. On the day the transaction was announced, Elizaveta Osetinskaia, the former chief editor of Vedomosti and Forbes, and the current chief editor of the news agency RBC, gathered friends together for a drink to Vedomosti. “We aren’t saying that everything will necessarily be bad—it's just going to be different," she told people. "But it will never again be the way it was.”

Demian Kudriavtsev declined to comment for this story.

Ilya Zhegulev

Moscow