A matter of taste

Moscow is now home to nine Michelin-star restaurants — but local foodies take the guide’s recommendations with a grain of salt

Russia’s gastronomic world was shaken in mid-October when the renowned Michelin Guide awarded Michelin stars to several Moscow restaurants for the first time ever. It was a long time coming for the country’s gourmands, who have hoped for the Michelin Guide’s recognition for over two decades. Seven restaurants received one star while two others received two stars, but no establishment received the coveted three-star distinction. In total, 69 Moscow eateries received a mention in this year’s Michelin Guide. For Meduza, food reporter Anton Obrezchikov breaks down who received stars, how they earned them, and why some people are critical of the whole affair.

In the early post-Soviet years, being aware of the Michelin Guide was a rarity and a mark of status for those in the know. Much ado was made about the romantic idea of the anonymous restaurant inspector, first popularized in Louis de Funès’ 1976 film “The Wing or the Thigh.”

The Michelin Guide first gained wider media attention in Russia in 2001, when the food magazine Restorator introduced it to readers. Back then, there were few candidates in Russia’s food scene deserving of recognition. The country’s only prominent chef was Anatoly Komm (the co-owner of the restaurants Russian Seasons and Anatoly Komm for Raff House, among others), who was then known for his first restaurant Green (located outside of Geneva), which soon closed.

Two decades later, Russia became the 33rd country to be profiled by the Michelin Guide. So far, Moscow is the only Russian city mentioned. The recognized restaurants received their stars at an awards ceremony attended by the city’s mayor, Sergey Sobyanin, and became a hot topic among those in the country’s restaurant and hospitality circles (and among its foodies). But the ensuing debate about the guide and the choices made by its experts lies not just in gastronomy, but in the broader problems facing the industry as well.

How does the Michelin Guide evaluate restaurants?

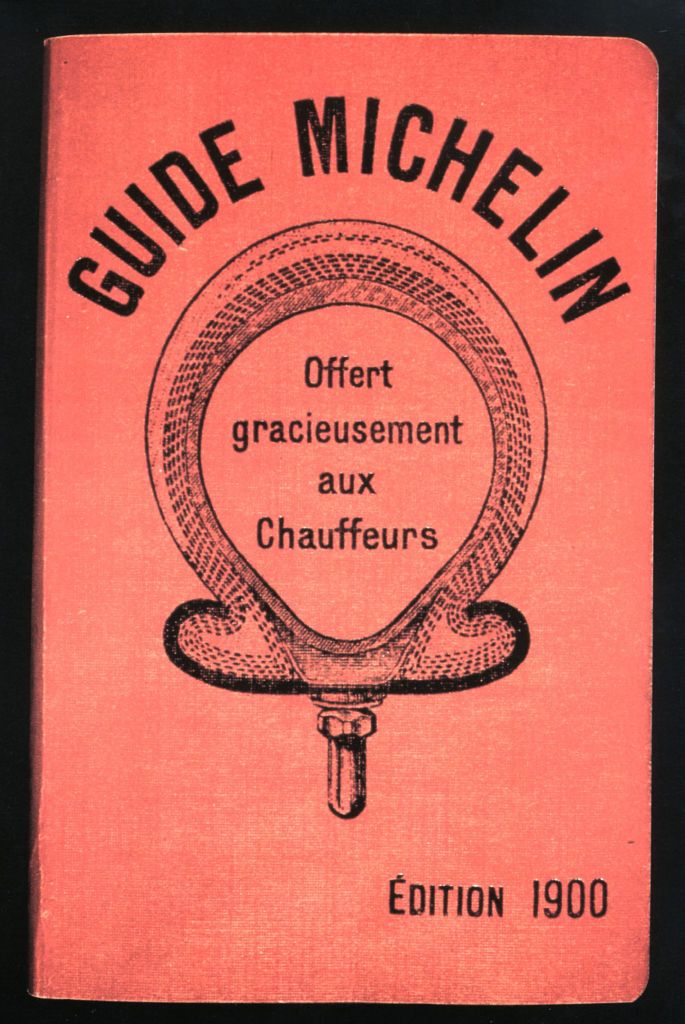

The Michelin Guide dates back to 1900. Its French publisher, the Compagnie Générale des Établissements Michelin SCA, is better known as the tire company Michelin. The Michelin Guide was created to serve motorists by providing maps and guides for them to use on road trips.

The restaurant reviews for which the Guide is known were originally a separate publication and began in the late 1920s. Its famous “star” rating system came out at this time as well — rating an eatery from one to three stars and including it in a broader list of recommendations.

A team of roving, anonymous inspectors are responsible for rating restaurants. These reviewers are not affiliated with other organizations and always cover their own bill at the restaurant. Most inspectors have a professional culinary background — for instance, they might be chefs, restaurateurs, or food critics. In awarding stars, different inspectors visit the same restaurant multiple times and pay attention to a set of criteria including:

- The quality of ingredients

- Harmony among the ingredients of each dish

- Skillful use of culinary techniques

- Consistent quality

- A chef’s unique flair

One star means that the restaurant serves very good food and should be patronized. Two stars are given to restaurants that the inspectors believe are worthy of a detour to visit. Three stars are reserved for those restaurants that are so distinctive that they deserve a special journey of their own.

Besides the stars, the Guide bestows a few lesser honors upon restaurants. The BIB Gourmand list selects restaurants with great food for reasonable prices (each region has its own threshold: $40 in the United States, 36 euros in Western Europe, etc.). There’s also a general list of eateries worth a visit, with no additional distinctions mentioned.

Which Moscow restaurants were honored — and why?

All total, the 2022 Moscow guide lists 69 restaurants. The guide is currently available online, but a paper edition is due out next year.

No establishment received three stars — which is to be expected, given that Russia’s restaurants are being evaluated for the first time. Still, two spots received the two-star distinction: brothers Ivan and Sergey Berezutsky’s Twins Garden, as well as the Chef’s Table concept at Arkady Novikov and Artem Estafiev’s ArtEst restaurant.

Twins Garden was an expected choice: Ivan and Sergey Berezutsky have spent many years perfecting their culinary craft and have already received scores of awards for their work, including on the world stage. Their Twins Garden restaurant is one of Russia’s most internationally renowned establishments — for instance, it was recognized in The World’s 50 Best Restaurants, which drew special attention to the Berezutskys’ unique vegetable wine, made up of tomatoes, carrots, parsnips, and leek.

On the other hand, ArtEst’s stars were more surprising — it just opened its doors in 2021, as Novikov’s take on haute-cuisine, and seemed designed to get on the Michelin Guide’s 2022 list. Its chef is intriguing too — Artem Estafiev was sent from Saint Petersburg to lead the new kitchen by Novikov, but little else is known about him — in large part because he himself maintains a mysterious image and is reticent to reveal much more. The Michelin Guide was impressed with ArtEst’s modern dishes, which were full of contrast and combined Russian ingredients with inventive techniques like fermentation.

Seven restaurants received one star, each with its own distinctive approach to the culinary arts. Beluga (by chef Evgeny Vikentiev and restaurateur Alexander Rappoport) is known for its breathtaking views and a lengthy vodka list. Biologie (by chef Ekaterina Alyokhina) distinguishes itself with a focus on organic ingredients. Grand Cru (run by chef David Emmerle with wines by the enoteca Simple) serves French fare alongside some of the world’s most prized wines. Savva (by chef Andrey Shmakov and restaurateur Arkady Novikov) crafts creative plates grounded in Russian cuisine — its signature dish is a borsch made with duck and cherries. The White Rabbit Family alliance of restaurants received a star each for Selfie (led by chef Anatoly Kazakov), Sakhalin (chef Alexey Kogai), and for the eponymous White Rabbit (chef Vladimir Mukhin).

Why have Michelin’s choices drawn criticism?

Receiving a Michelin star is a major distinction both for the chef and for their restaurant. But judging by the list of Moscow’s Michelin-starred establishments, having an outstanding chef is not sufficient for a restaurant to be included. Nearly every eatery that received a star worked diligently to secure a spot in world ratings — not just in the Michelin Guide, but in others like The World’s 50 Best Restaurants ranking. The majority of star recipients were members of large gastronomic holding companies with considerable marketing resources at their disposal. In particular, this describes the White Rabbit Family (WRF): three of their restaurants were honored with stars at once.

For this reason, many in Russia’s culinary scene were disappointed by the Michelin Guide’s inaugural decisions. It confirmed for many that even the most talented and creative chefs competed on an uneven playing field from the start. They have few ways to match the lobbying of corporate behemoths who could reach Europe’s “culinary bureaucracy,” which in reality has a poor grasp on the nuances of Russian fine dining.

The Guide’s general list of restaurants, where no stars are awarded, is more representative of Moscow’s restaurant landscape. The choice of eateries here is eclectic and it’s tough to find a pattern in how they were chosen. One can find a variety of spots including Pushkin (which received no stars), Natakhtari, Wine Religion, Expeditsiya, Doctor Zhivago, Hedonist, and Fahrenheit — 45 restaurants in all.

Given the fluid and unpredictable nature of Moscow’s restaurant scene, the list is already a bit outdated: the restaurant Volna, which secured a spot on the list, is now temporarily closed (per its website). The Guide also lists Pushkin as a seafood spot, even though this has never been the case.

The Michelin Guide also publishes its BIB Gourmand list, where one can dine for around 2,000 rubles ($28) a person. The 15 restaurants chosen have evoked less controversy than the big names and are much more accessible.

Finally, three Moscow restaurants received a green star, which are awarded by the Michelin Guide for excellence in sustainable cuisine. This year’s recipients were Biologie, Björn, and Twins Garden — the only establishments in town that source ingredients from their own farms.

Sustainability — usually defined by working with ethical suppliers, using local products, and reducing waste — is prized in the West, even in fast food. But in Russia this concept never became mainstream, owing much to the complex logistical difficulties involved in obtaining local produce.

Finally, two establishments were recognized in other categories. Björn’s Nikita Poderyagin was named the best young chef for “masterfully fusing passionate emotion with refinement in the kitchen to the delight of his guests.” And Twins Garden got another mention — this time, they were honored for having the best service among the nominees.

Why might Russia’s smaller cities not get a visit from the Michelin Guide?

The Michelin Guide’s Moscow recommendations hardly broke any new ground for the city’s foodies. Only a few picks on the list were truly unexpected. For example, Chemodan, a restaurant specializing in wild game and Siberian dishes, has been around for a decade and has cultivated its own niche audience. For most Muscovites, Chemodan’s fare is not particularly interesting, while it might be a bit too exotic for the visiting tourist.

A spot in the Guide is a major marketing asset — not just for the restaurant, but also for the city that hosts it, which usually hopes to attract tourists. It’s unclear how involved Moscow’s city administration was in the Michelin process, but judging by mayor Sergey Sobyanin’s speech at the awards ceremony, the city has a keen interest in attracting global attention to Moscow’s gastronomic scene. He made a point of thanking Michelin for their “moral support” (somewhat ironic, given that Moscow’s restaurateurs often bemoan Sobyanin’s erratic and inconsistent pandemic restrictions).

So far, Moscow is the only Russian city in the Michelin Guide. Saint Petersburg is a possible candidate for future inclusion. In an interview with TASS, the director of the Michelin Guides Gwendal Poullennec explained that he expects to explore more Russian destinations in the future, though he did not specify any cities where Michelin’s inspectors might venture next.

Over the decades, the landscape of global rankings and reviews has seen fundamental changes — perhaps making guides like Michelin’s less and less relevant. Central to these shifts is the crucial role of social media, which dilutes the importance of any given author, while simultaneously creating a class of influencers who thrive in speaking to a narrow and specific audience. The Michelin Guide is taking steps to chase this trend — for instance with their newly introduced Green stars.

Story by Anton Obrezchikov

Translation by Nikita Buchko