‘Indifference is our main problem’

Artist and activist Yelena Osipova on Russia’s war against Ukraine and her 20 years of protesting Putin’s regime

They call her “the conscience of St. Petersburg.” For twenty years now, 76-year-old Yelena Andreyevna Osipova has been protesting war and the Russian government. An artist and teacher by training, Osipova spent her career teaching children to draw. These days, she brings her anti-war posters out to St. Petersburg’s central streets. In March 2022, she was arrested several times and footage of Osipova surrounded by riot police went viral online. In an interview with Meduza, Yelena Osipova talked about political protest, art, the Putin regime, and Russia’s future. This is her story in her own words.

‘When the war started, time stopped’

On February 24 in the middle of the night, I got a call from a woman, probably a journalist, who wanted to know my thoughts on what was happening. I get occasional calls asking my opinion on this or that event. I said that the Russian Führer had started his Anschluss and that I’d been expecting as much for a long time. Already in 2014, it was obvious to me where [Putin’s policy toward Ukraine] was heading. The majority of my anti-war posters date to that period. But no one believed that something like this could happen.

That same day [February 24], I went out in downtown St. Petersburg with a poster that said: “O mania, O mummy of war! You’ll burn, Russia! Madness, madness you make!” This is a poem by Marina Tsvetaeva. Of course, she was writing about Germany, whereas I changed the text to make it about Russia. I had originally made that poster after the murder of Boris Nemtsov [on February 27, 2015].

On February 24, I went out to protest feeling totally hopeless, but I met people who encouraged and inspired me. Lots of people were out in the streets that day. I stood near the Catherine II monument [on Ostrovsky Square], and they were running from the police down Nevsky Prospect shouting “No war!” Some of them managed to run up to me with words of gratitude and support. A few men came up crying and asking: “What can we do? How can we help Ukraine?” All of that gave me a huge boost. I saw that many people were opposed [to Russia’s actions in Ukraine].

At first I wanted to continue on to Gostiny Dvor, but there were lots of police there and I would have been taken away immediately. So I stayed put, and ended up standing there for quite a while. But the police did eventually show up. A couple of journalists managed to run up and take photos of my arrest. People tried to intervene, but I asked them not to — I was worried they’d be taken away for their troubles. The police put me in a car and drove me home. Their parting words were that I should stay off the streets.

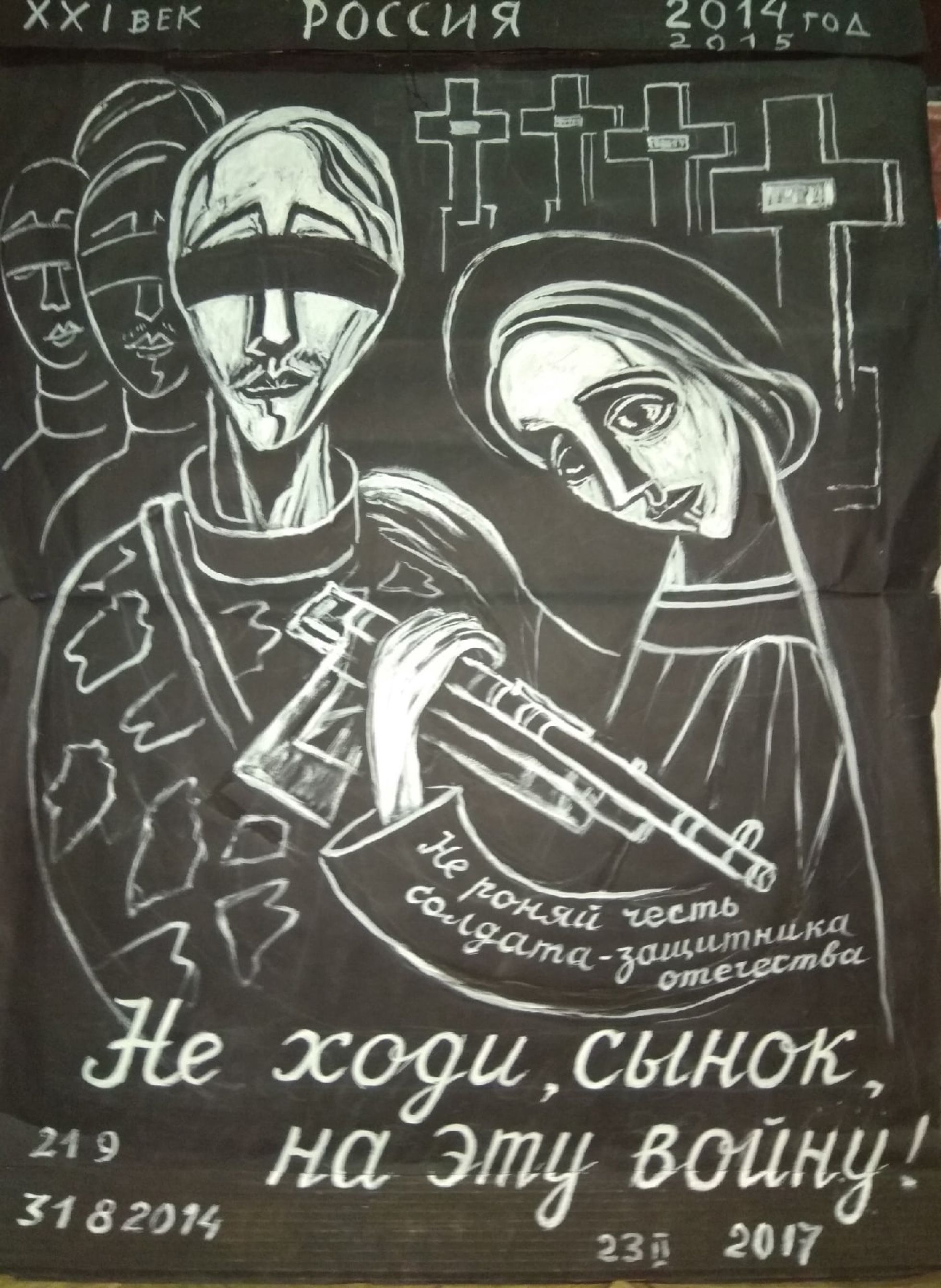

I try to go out [to protests] as much as I can. My health doesn’t always let me, my medication is the only thing keeping me going. Another time, on [February 27], I went out with a poster where I’d drawn a blindfolded soldier. His mother is taking away his weapon and saying, “Don’t fight in this war, son.” To which I’d added: “Soldier, lay down your weapon, don’t shoot — that’s what makes a true hero.” Because that’s what constitutes real heroism in the current situation. Getting court martialed is better than murdering Ukrainian civilians.

Then I learned that people were planning to come out in force near Gostiny Dvor [on March 2]. And I decided to join them. I brought another poster I’d created long ago, on the theme of nuclear weapons. Some days earlier I’d heard [Ukrainian president] Zelensky discussing the need for nuclear weapons. That really alarmed me. My poster says that, on the contrary, we need to start talking about global disarmament and the immediate prohibition of nuclear weapons. They’re such a terrible danger!

I still haven’t taken down my Christmas tree. Usually it’s gone by [International Women’s Day] on March 8, but when the war started, time stopped and the Christmas tree slipped my mind entirely. I don’t only make posters, I also paint. I’ve got a stack of unfinished paintings lying around that I was preparing for an exhibition. But now posters are the only thing I can bring myself to make.

‘The country was asleep’

The first time I came out with a protest poster was in 2002. That was during the [Second Chechen War], when the hostage crisis happened in Moscow’s Dubrovka Theater. Like everyone else, I watched events unfold on live TV. Some of the footage has really stuck with me — I remember how, after pumping an unknown chemical agent into the theater, [the Russian authorities] brought out a young woman, a hostage. She was unconscious, with a huge braid. They carried her carelessly, like a bunch of firewood, letting her braid flop around behind her.

That was when I realized I couldn’t stay silent any longer. I took a piece of poster board and wrote on it: “Mr. President, change course immediately!” And I went out with that simple hand-written poster and stood next to the Mariinsky Palace. No one was protesting at the time, and no one came to join me. I stood there alone for a long time — back then they hadn’t yet gotten into the habit of arresting people just for protesting. But I got no reaction and no support, either.

Then there was the even more horrific Beslan [school siege that began on September 1, 2004]. I made a poster that said: “Mothers of the world, give birth to little princes, they will save the world!” That, too, got almost no reaction. Only the parents of the children who perished came out into the streets. On the whole, the country was asleep.

That indifference is our main problem. We’re too late. If people had come out and protested from the beginning, maybe everything would have turned out differently. I am surprised by this level of obedience. After all, we’re not living in an era where someone denounces you and you instantly get a bullet to the back of the head. I can still remember my painting instructor at the N.K. Roerich Art School [in St. Petersburg] telling someone who couldn’t muster any boldness in her work, “What’s there to fear in your own country?” This was someone who had experienced all the horrors of the Stalinist period. And yet that was how she talked.

There are lots of good people, lots of people who understand what’s happening. But they’re full of fear. And I don’t judge them, of course. I know they’re afraid of losing their jobs, their money, even their freedom. I’m the one who has nothing to lose. I could die at any moment.

‘I never sell my political art. If I did, no one would trust me’

I’ve been drawing practically my whole life. My grandmother worked as a security guard in the Russian Museum and, when I was little, often took me to work with her. My mother worked day and night at the time, and there wasn’t anyone to watch me. So, from the age of three, I ran all around the Russian Museum and examined the paintings. One of my favorites was Alexander Ivanov’s “The Appearance of Christ Before the People.” I’d lie down on the floor in front of that painting and study it for hours.

I went on to the N.K. Roerich Art School, which used to be called Tavricheskaya [Art School]. I taught for a long time, I helped start three art schools from scratch. I taught children to draw right up until I retired. In 2009, my only son died, and that’s when I stopped teaching: children need to see smiling faces, and I couldn’t smile anymore.

I’ve keep all of my posters. People have tried to buy them from me many times, but I’ve always refused. I don’t sell my political art. If I did, no one would trust me. As it is, I’m constantly being accused of protesting for money. I feel I’m only entitled to sell my paintings, never my posters. I did hear that people have taken to selling photos of my political works, but I myself have never sold a single poster, and don’t plan to. I still have them all, with the exception of those I couldn’t rescue from the police station. I have over a hundred posters in my house, though I haven’t counted them.

I’ve been taking my posters out into the street for 20 years now. I’ve been through it all: arrests, overnight stays in jail, trials, fines. But there’s nothing they can take from me now. My pension is just 6,000 rubles [$74 at today’s exchange rate] per month. People will often come right up to me in the street and offer money, but I can’t accept it. A few years ago they raised 5,000 rubles to pay a fine for a protest I’d been in, but I donated that money to the defendants in theBolotnaya Square Case. I can’t accept any money, only supplies for my posters. People have been bringing me paints and cardboard recently. The kind they use to pack furniture works the best: it’s big and easy to fold. Store-bought cardboard just breaks when you try to fold it. Anyway, that’s the only material help I can accept.

‘My poor, beloved Russia’

Everything was clear to me from the very beginning, as soon as [Boris Yeltsin] appointed [Putin] his successor. All that stuff about “whacking [terrorists] in the outhouse,” and all the speeches that followed — that told me everything I needed to know about [Putin’s] government. Members of law enforcement should never occupy positions of real power.

I’d seen many Soviet rulers in my day, but they were totally different. They had their faults, to be sure, but the current leadership has certainly surpassed the old methods. [Putin and his people] have built an entire system for themselves, they hoard money and spend it only on weaponry. They’re inculcating even the youngest generations with militarism. They put kids in military caps, but rarely do you see dove imagery anymore. It’s as if there haven’t been horrible wars before, as if they’ve forgotten everything. And all around us are the government’s disciples. I blame them, too: they support the state and turn people against peace. They brag about murdering people!

When I used to watch TV, it was mainly Russia-K [the culture channel], but now even that’s dominated by the ideology of the “Russian world.” As for the radio, I’m afraid even to turn it on. I used to listen to Echo of Moscow, but now that’s been replaced by [the state-run] Sputnik Radio, where you can hear some truly nightmarish things. I avoid tuning in so I don’t get upset. The only place to find anything anymore is online. After one of my exhibitions, someone gave me a computer, which I had to learn how to use. That’s where I try to find information to share with the youth — films, videos, articles, and so on. Like [Mikhail Romm’s 1965 film] Ordinary Fascism. That’s something everyone should watch.

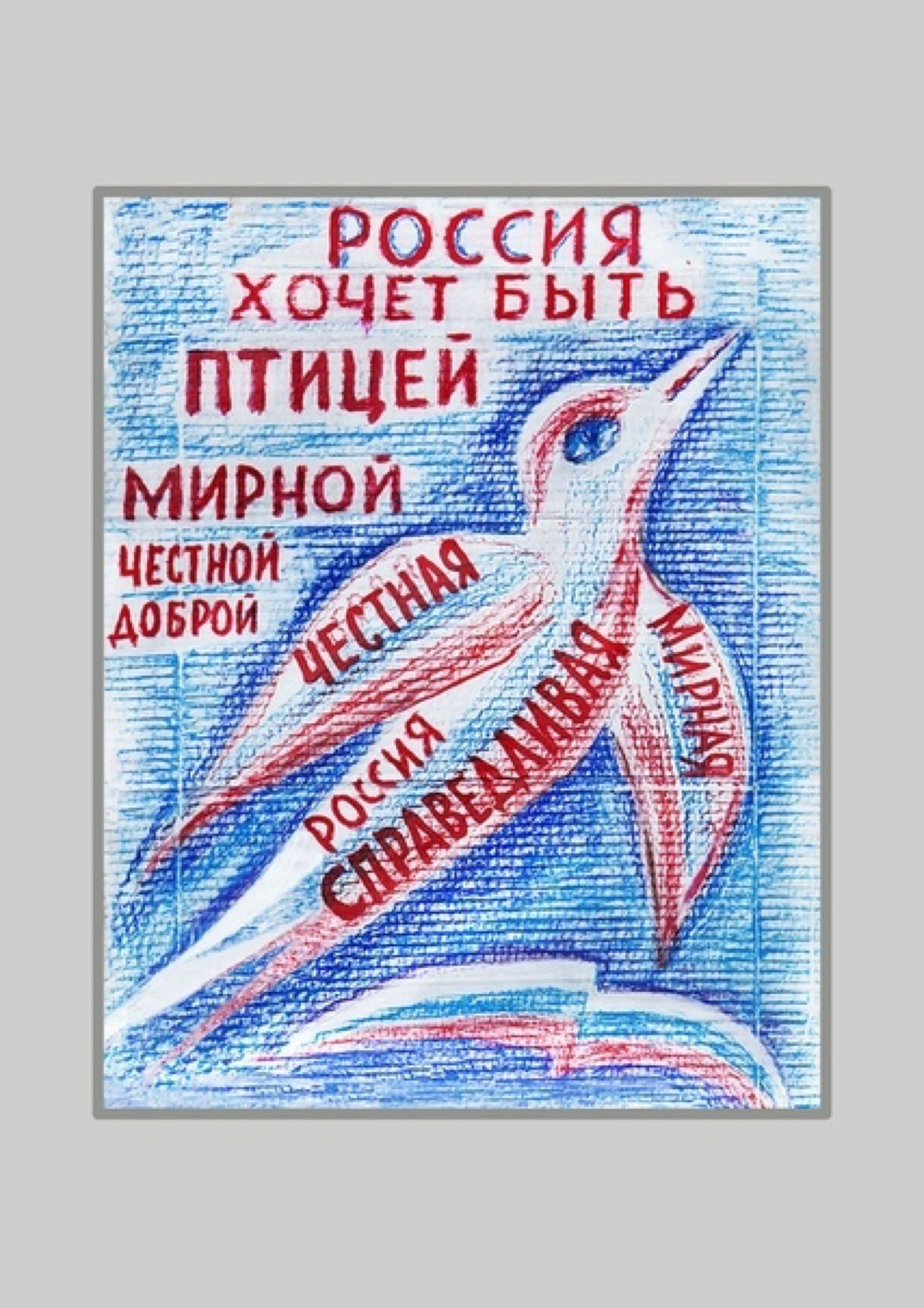

I always imagined Russia as a bird. A bird that wants to be peaceful and free. My poor, beloved Russia, you just can’t seem to get there. I still love this country, which has produced so many talented people and given so much to world culture. I never wanted to leave, even when people offered to help me do so. But today [Russia’s] ideals have changed: it’s all about owning everything, subjugating everyone, annexing as much [territory] as possible.

The question that’s being decided right now is: How much longer can the current government survive? The fate of Russia is being decided — and the rest of the world, too. Maybe the horrors that have come to pass will let us pivot somehow. I try to believe and give people hope. How else can you keep living?

Interview by Evgenia Sozankova

Translation by Maya Vinokour