Bashar al‑Assad’s fall and Russia’s army. How Syrian government’s collapse will reshape Russia’s presence in Africa and the Middle East

The new Syrian authorities have taken full control of Tartus and Latakia, two cities hosting key Russian military facilities: the Khmeimim airbase and the naval base at the Port of Tartus. “Thousands” of Russian troops remain in Syria, according to Kremlin-aligned channels. While the new regime has not attacked these bases, it is unlikely to tolerate their indefinite presence. The evacuation procedure for Russian forces—if it happens—remains unclear. Compounding the challenge, Russia’s operations in Africa, formerly supported by Wagner Group mercenaries, are heavily reliant on the logistics network from the Syrian bases. This includes operations to back West African regimes, Sudanese factions in its civil war, and the regime in the Central African Republic.

Russian forces have been stationed in Syria since 2015 under a long-term agreement allowing them to stay until at least 2066. That agreement, signed by now-ousted Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, unravelled rapidly as Assad lost power and sought political asylum in Russia.

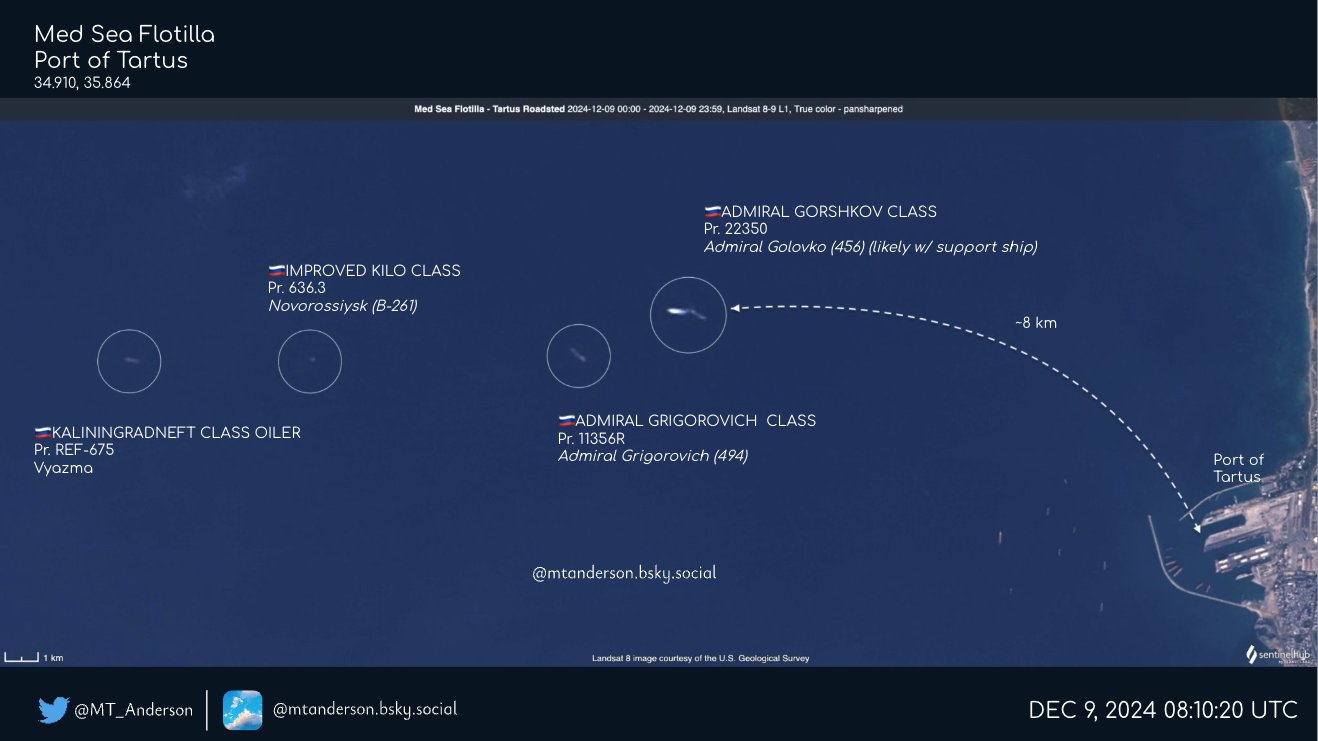

Military analyst Kirill Mikhailov believes Russia will ultimately have to withdraw its troops. Reports of Russian ships leaving Tartus began circulating a week ago. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov initially claimed the movements were part of routine drills, but satellite images published on December 9 by OSINT analyst MT Anderson revealed that the vessels had moved eight kilometres offshore.

A Landsat satellite image confirms that Russia’s Mediterranean fleet is idling in a holding pattern approximately 8 kilometres west of the Port of Tartus. Photo: MT_Anderson / X (ex-Twitter)

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov stated that the future of Russian bases would be determined in negotiations with Syria’s new government. However, he suggested it was too early to make predictions. This uncertainty contrasts with recent declarations by the Russian Ministry of Defence, which said its forces were continuing to “support the Syrian Arab Army in repelling terrorist aggression” and claimed to have killed “hundreds” of militants.

Mikhailov is skeptical about Moscow’s prospects in Syria: “Considering the new regime’s policies and Russia’s, so to speak, rich history with the Syrian opposition—especially the bombings—it’s hard to see the government accepting Russian bases on its soil.” He dismissed a more radical Russian proposal to establish a “Latakia People’s Republic” as doomed, citing the hostile mood among local residents, who have been toppling statues of former leader Hafez al-Assad.

Anas al-Abdah, a senior figure in Syria’s National Coalition of Opposition and Revolutionary Forces, told journalists from Russian state media that Syria’s new authorities aim to “maintain good relations with Russia” and are focused on “strategic partnerships with regional and global countries to rebuild Syria for all its citizens, regardless of their ethnic or religious backgrounds.” However, he did not comment on the fate of the Russian military bases.

Mikhailov sees a safe withdrawal of Russian forces as plausible for now. He notes that while the new government has advocated the removal of all foreign troops—including those of Turkey and the United States—it seems to be prioritising Syria’s reconstruction and avoiding direct confrontations with its neighbours.

According to the analyst, withdrawing Russian troops is currently the most pragmatic choice—“the best of the bad options” available to the Kremlin. After that, Russia will likely have to abandon any hope of maintaining military bases or logistical hubs in Syria for decades to come.

Fighterbomber, a Russian army-linked Telegram channel posting about military aviation, also takes a grim view of the chances of retaining the Syrian bases. It notes that the new government has “zero need” for them, although it does not foresee any immediate threats to Russians.

“Russian troops were stationed across all of Syria, numbering several thousand soldiers and dozens of pieces of equipment. A couple of days ago, they all redeployed beyond the mountains, closer to the coast, where they are now awaiting further, er, relocation. Since, as always, they were prepared for anything, some isolated units now find themselves encircled, holding defensive positions as they wait for support or an exit corridor. I believe they’ll be fine, as the higher command has effectively ceased combat operations and is negotiating safe passage,” the channel wrote yesterday.

The channel’s author argues that there is no reason for Syria’s new authorities to resort to any extreme measures: “There’s no sense to it.”

“When I fought there, Syria was a different place. Yes, the country was bled dry by a five-year war, and yes, the mukhabarat used to drive farmers and workers into the army with sticks, but they fought. There were units that fought with real bravery. And there were Syrian pilots who, flying their clapped-out machines, showed us how to drop makeshift gas cylinder bombs into tank turrets without any of your fancy GPS or lasers. Back then, ISISoids were executing people by the hundreds and thousands—Muslims, Christians, everyone—on camera. Back then, we were needed and welcomed,” the pilot wrote in a separate post, tinged with nostalgia. “Today, nobody there fucking needs us. We still need Syria, but Syria doesn’t need us.”

A Complicated Exit

The logistics of evacuating personnel and equipment pose significant challenges.

Turkey’s closure of the Bosporus and Dardanelles to Russian ships after Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine complicates the withdrawal of naval assets from Tartus. According to Dara Massicot, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Russia may face a long journey to its Baltic ports or have to seek temporary harbours in countries like Libya, Sudan, or Algeria.

Removing forces from Khmeimim airbase will also require substantial effort. Massicot estimates that “hundreds of sorties” by Il-76 and An-124 transport aircraft will be necessary: “When Russian forces deployed to Syria in 2015, they flew almost 300 sorties in two weeks, and that was before base expansion.”

Fighterbomber channel pointed out that international airspace permissions will be a hurdle. “To relocate aircraft, you need approval from countries whose airspace you cross. Such approvals can take weeks,” the channel warned.

Implications for Russia’s Africa Presence

The Syrian bases have not only served Moscow’s operations in Syria but also functioned as a critical hub for supplying Russian mercenaries and proxies in Africa. Losing Khmeimim could undermine Kremlin-backed operations in places such as Libya, the Sahel region, and the Central African Republic.

“This significantly undermines Russia’s influence in the Middle East and also casts doubt on its standing in Africa, where Moscow continues to support General Khalifa Haftar’s regime in Libya, several juntas in the Sahel region of north-west Africa—where various Russian mercenaries assist in combating al-Qaeda and Tuareg separatists—as well as other projects like the Central African Republic, Sudan, and so on,” military analyst Kirill Mikhailov confirms.

The key question for Russian forces now is whether heavily loaded transport aircraft like the Il-76 or An-124 can “technically make it to the airfields in Libya currently under Russian control,” Mikhailov told Mediazona. A second question is whether Khalifa Haftar is sufficiently dependent on Kremlin support to grant Russia a naval maintenance facility similar to Tartus—perhaps in Tobruk, a Libyan city on the Mediterranean coast with a major seaport.

Who is Khalifa Haftar

General Khalifa Haftar leads the Libyan National Army (LNA), a faction that controls eastern Libya, including the major city of Benghazi and a substantial stretch of the country’s coastline. The port city of Tobruk, a key Mediterranean seaport, is also under Haftar’s authority.

Haftar commands one side in Libya’s prolonged civil war, which has flared up repeatedly since the collapse of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in 2011. In 2020, a ceasefire was brokered between Haftar’s forces and the factions governing the western regions, including the capital, Tripoli.

Haftar’s military career began as a participant in the 1969 coup that brought Gaddafi to power. Once a trusted officer in Gaddafi’s regime, Haftar oversaw Libya’s disastrous invasion of Chad, during which his forces were encircled and forced to surrender. Gaddafi disavowed the troops, denying they were part of his army. After this debacle, Haftar moved to the United States, where he spent 20 years and obtained American citizenship.

In 2011, Haftar returned to Libya but failed to secure a prominent political role. However, in 2014, he launched a military coup that reignited the country’s civil war. In September 2023, Haftar visited Moscow following a trip to Benghazi by Russian Deputy Defence Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov. During his Moscow visit, Haftar held meetings with both Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu and President Vladimir Putin, an honour that positioned him as a quasi-head of state in Russian eyes.

Wagner PMC has been operating in Libya since at least 2021 and has played an active role in supporting Haftar’s forces. Internal documents from Wagner reportedly referred to Libya under the codename “Lipetsk.” In 2018, a notable video surfaced showing Wagner’s founder, Yevgeny Prigozhin, seated at the negotiating table alongside Haftar, Shoigu, and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov.

At 81, Haftar has survived premature reports of his death. In April 2018, Russian media outlets RIA Novosti and Kommersant incorrectly announced his demise. In truth, Haftar had suffered a stroke and received treatment in France. According to Stephanie Williams, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, power within Haftar’s faction is now gradually shifting to his sons, Saddam and Khaled.

“From Russia’s perspective, the answers to these questions may well be favourable, as Haftar has no reason to antagonise Moscow right now,” speculates Kirill Mikhailov. “After all, the internationally recognised government is not Haftar’s administration, but the one based in Tripoli in the west of the country. However, there’s also the matter of other regional players who wield influence over Haftar, namely France, Italy, and the United Arab Emirates.

As a result, he stresses, both the logistical and political questions remain unresolved. “This doesn’t mean the entire structure of Russia’s presence in Africa will collapse tomorrow, but it does place it under considerable uncertainty.”

Editor: Dmitry Treschanin