The double status problem. Anarchist mathematician Azat Miftakhov on his life at the bottom of Russia’s brutal prison caste system

On August 5, Russia’s Supreme Court rejected the final appeal for Azat Miftakhov, a mathematician and anarchist serving his second politically motivated prison sentence. His latest conviction, for “justifying terrorism,” rests entirely on the testimony of a fellow inmate who claimed Miftakhov had praised an attack on the security services. For over six years, Miftakhov has navigated two coexisting identities in Russia’s brutal penal system: that of a political prisoner and a member of the “obizhennye”, or the “degraded”—the untouchable caste at the bottom of the prison hierarchy. In letters from behind bars, he tells Mediazona how he survives.

Azat Miftakhov, 31, was a graduate student in mathematics at Moscow State University when he was first arrested in February 2019.

Initially accused of making explosives, he was beaten and tortured by security service agents who threatened to rape him with an electric screwdriver. Another detainee was tortured with an electric shocker by security forces who demanded he incriminate the mathematician. After his detention, Miftakhov attempted to slit his wrists but gave no confession.

Bespectacled, short and soft-spoken, the anarchist has not yielded to this day, despite pressure from the FSB and a second fabricated terrorism case.

Back in February 2019, when the security forces failed to find evidence that the young man had been making explosives, Miftakhov was accused in a case concerning a window broken a year earlier at a ruling “United Russia” party office in Moscow’s Khovrino district.

The pressure campaign continued inside the prison. Officers from the FSB informed other inmates of Miftakhov’s bisexuality. The move was a calculated effort to have him ostracised and forced into the “degraded” caste, a group subject to constant humiliation, violence, and forced labour. Miftakhov did not deny the officers’ words; back in 2019, intimate photos of him were published by Telegram channels linked to security services and later by the state-run TV channel Rossiya-1.

A vigorous public campaign in support of Miftakhov began from the first days of his arrest, so he could not hide his status as a political prisoner from other detainees, though he did not deliberately advertise it.

“During mail call, the whole prison section is standing in formation,” he explains. “An activist comes up with a stack of letters. The first is for me, the second for me, the third, the fourth… In the end, only two or three letters go to other inmates. The rest are mine.” He often received letters and postcards from France, Germany, and Sweden, something extraordinary for other prisoners. “They’re writing even from America!” they would marvel. The camp’s population changed, but newcomers would often approach me and ask: “Is it true that Oxxxymiron wrote a song about you?”

—

In the winter of 2021, Azat Miftakhov was sentenced to six years in a penal colony. A secret witness, interrogated a year after the case was opened, claimed to have identified Miftakhov among the group that broke the “United Russia” office window and threw a smoke bomb inside, recognising him by his “expressive eyebrows.” The anarchist himself denied any involvement in the action.

After his time in Moscow’s pre-trial detention centres, Miftakhov was transferred in August 2021 to serve his sentence at Penal Colony No. 17 (IK-17) in Omutninsk, Kirov region. The prison was “red”, or tightly controlled by the administration through “activists” from among the prisoners.

Although severe physical violence had become a rarity there in recent decades, the colony’s reputation for torture dated back to the late 1980s, especially as punishment for refusing to prepare for official holidays. For many years, the most important of these was Victory Day, and all prisoners without exception were required to participate in preparations for a “parade” featuring models of military equipment.

“It was considered an absolutely mandatory thing, and to refuse meant condemning yourself to unimaginable torment: torture with shockers, bleach, and the punishment cell,” recalls Timur Isayev, who was incarcerated in IK-17 at the same time as Miftakhov. He was serving a sentence for organising an escort agency. After his release, Isayev left Russia.

Miftakhov impressed Isayev immediately upon his arrival at the colony. The inmates learned that during quarantine, security officers had offered the mathematician the chance to “hide” his “degraded” status in exchange for cooperation, but he refused.

“He told them: ‘Chief, you protect laws and rights, yet you speak to me in some kind of criminal jargon that you yourself are supposed to fight against. I don’t recognise your stinking ponyatiya. I don’t recognise this division of people either. Do what you think is necessary.’ The cops were just stunned by such audacity and directness,” Isayev recalls.

Thus, from the perspective of the other prisoners, Miftakhov had essentially “defined” himself as “degraded”, since he had the opportunity to hide his status, explains the source to Mediazona. Therefore, each of muzhiki, or “the men”, regular prisoners, had to decide for himself whether it was appropriate to communicate with him. Isayev says he spoke with him without regard for others: “He had a normal social life in the zone, he was treated very well—not like the others in that caste, with whom he could still interact. He had a completely special position.”

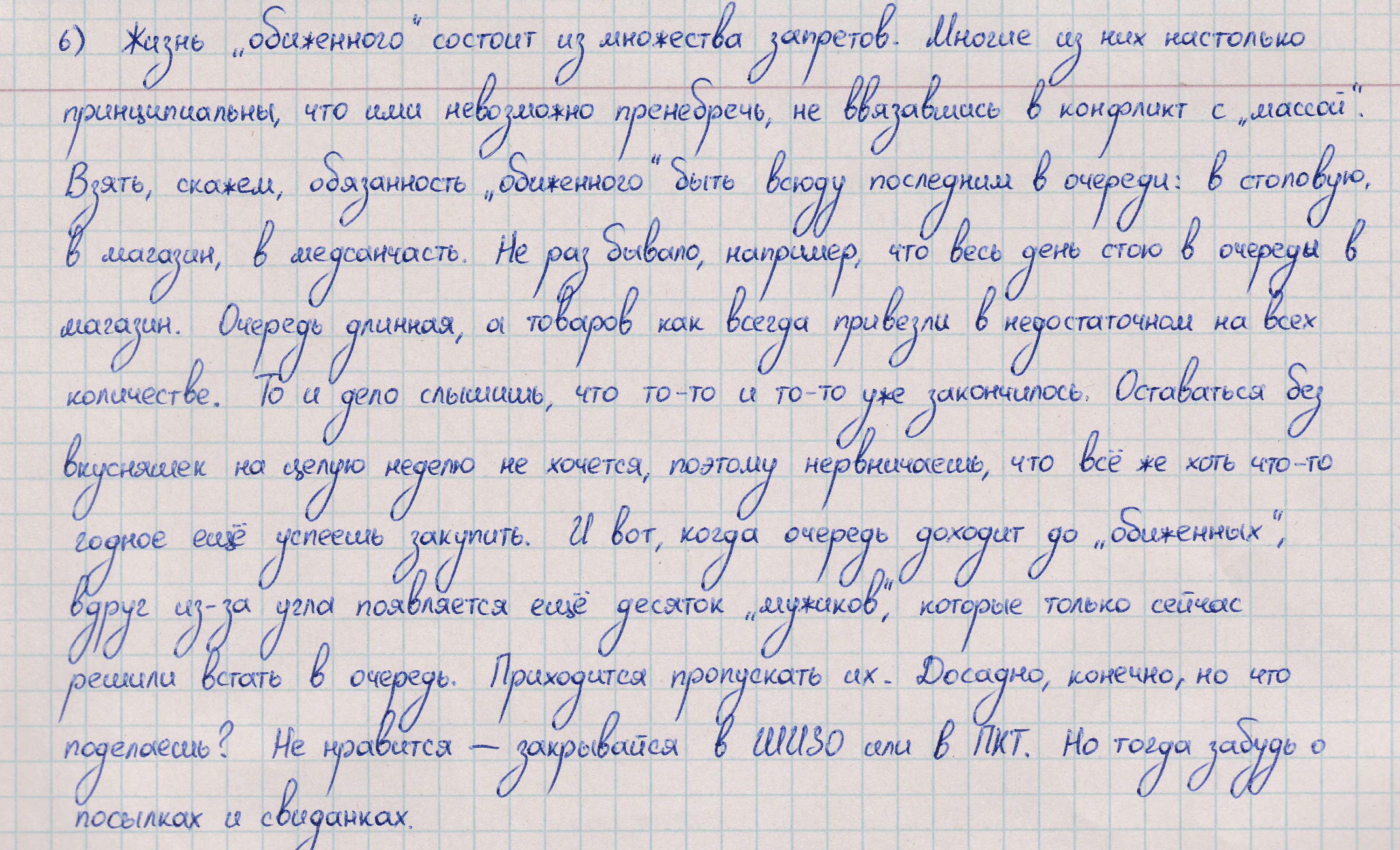

From Azat Miftakhov’s letter to Mediazona (abridged)

You can’t get “infected”’ by talking to someone who is “degraded”, but it’s considered improper for one of “the men” to hang around a “degraded” person for too long. You won’t be “called to account” for it, but you might catch ridicule and taunts from others, even provocations. They might suggest that a “man” “share” living quarters with the “degraded” since he gets along with them so well.

The life of a “degraded” person consists of many prohibitions. Many of them are so fundamental that they cannot be ignored without getting into a conflict with “the men”. Take, for example, the obligation for the “degraded” to be last in every queue: for the canteen, the shop, the medical unit. It happened more than once, for instance, that I’d stand in line for the shop all day. The queue is long, and as always, they’ve brought in an insufficient amount of goods. Every now and then, you hear that this or that has already run out. And then, just as the queue reaches the “degraded” inmates, a dozen more of “the men” suddenly appear from around the corner, having only just decided to join the line. You have to let them go first. It’s frustrating, of course, but what can you do? If you don’t like it, you can get locked in a punishment cell or a cell-type unit. But then you can forget about parcels and visits.

There is only one prohibition that I refuse to accept—the ban on fighting one of “the men”. If someone tries to humiliate my human dignity with an insult or by forcing me to do something, I consider it my sacred right to respond with force. The only thing I have to be wary of when exercising this right is punishment from the activists or the criminal elites. They can beat you severely for it, causing serious injury. However, I value my human dignity too highly to allow it to be debased, even under the threat of injury. Prison is a place where you’d better not “swallow” humiliation. If you “swallow” it once, you convince those around you that you can “swallow” it again and again. It’s better to nip it in the bud. That’s my philosophy on the matter.

I have had to fight “the men” several times, and each time it was over my status. It didn’t always lead to a scandal. Sometimes we managed to make peace with my opponent afterwards. A couple of times, a “case” was brought against me. The “trial” took place in a storeroom. Activists and various influential people as “judges” would cram in there, along with both sides of the conflict, meaning me and my “victim”. Witnesses were also called. Some “judges” seemed eager to pass a harsh sentence, which could have been carried out on the spot. I had to be prepared for such a turn of events and at the same time maintain my composure while justifying my position. Although according to the “prison” law, I was already in the wrong from the start, so my universal human arguments were unlikely to work there.

Fragment of Miftakhov’s letter to Mediazona

—

Miftakhov’s principles faced a major test in the spring of 2022, as the colony prepared for its annual Victory Day parade.

When Miftakhov saw other prisoners painting the “Z” and “V” symbols of the Ukraine invasion onto military props, he informed his detachment chief he would not participate. He expected to be sent to a punishment cell, but the administration, wary of his high profile, opted for a different strategy.

The day before the parade, Miftakhov was summoned; he expected to be tortured there, but instead, an inspector led him to a windowless room hidden deep within the medical unit, furnished only with a bed, a bedside table, and a toilet. Soon, the head of the operational department arrived. He explained that the room would temporarily become a “safe place” for the political prisoner.

From Azat Miftakhov’s letter to Mediazona (abridged)

“We’ve received information that some convicts are unhappy with your position,” the officer told me. “They want to teach you a lesson.”

“Therefore,” he continued, “it was decided to provide you with a safe place. Due to the threat to your health.”

“And how long will I be in this safe place?” I asked.

“Well,” the officer seemed to ponder, “I don’t know. Maybe a month, maybe a year. Or maybe until the last convict who wants to beat your ass is released.”

After talking with me a little more, he left, and I remained in that room. That’s how I began to learn what a “safe place” was. And I must say, it was the best gift the IK-17 administration could have possibly given me.

From then on, I didn’t have to go to work. I could spend all day on self-development, solving math problems and reading books. But most importantly, I could rest from the constant hustle and bustle of the common area. I wished it could last until my release. However, my happiness was not destined to last long. A week later, some random people were asked to sign off that the threat against me was gone. I had to return.

—

It was in IK-17 that Miftakhov formed a friendship with Evgeny Trushkov, another “degraded” prisoner serving a long sentence for charges including group rape. This friendship would prove to be his undoing. As Miftakhov’s release date in September 2023 approached, the FSB scrambled to build a new case against him. Trushkov became their star witness.

He testified that Miftakhov had “justified terrorism” in conversations with him, allegedly praising Mikhail Zhlobitsky, a teenager who bombed an FSB office in 2018. “I admire the actions of Mikhail Zhlobitsky, who was not afraid to lay down his life in the fight against Putin’s regime,” Trushkov claimed Miftakhov had said.

From Azat Miftakhov’s letter to Mediazona (abridged)

In the two years we knew each other, I received nothing but support from him. Sometimes he would tell me how he wanted to help me evade the FSB’s attention, that he was even willing to postpone his own freedom for it. Some of his suggestions were naive, which only convinced me of their sincerity. So when I found out that Trushkov had testified against me, I didn’t believe it at first. Only gradually, as I got acquainted with my new criminal case, did I begin to understand that he had betrayed me.

I do not think Trushkov initiated the criminal case, as he claimed in court. I am sure his story about how he, out of patriotic feelings, went to report the alleged crime to the detachment chief was fabricated to make the prosecution’s evidence seem coherent.

I believe this is what happened. On July 20, he was presented with a choice: either you give us the testimony we need against Azat, or you get “spun up” with him on a terrorism charge, but a more severe one. And they probably made it clear that the necessary witnesses for such a charge would be found. From there, I see two possible scenarios. First: he got scared for himself. Second: he made a deal with the FSB for my own good. I do not rule out either of these options, nor do I justify them.

Making deals with the FSB is a losing game from the start. One should not think that you can outsmart them this way, gaining more than you lose. Such underestimation of the enemy is extremely dangerous. Once you make one concession to them, they will force you to make a second, a third, and so on, until you give them your soul. In my conversations with him, I noticed this naive underestimation of the special services.

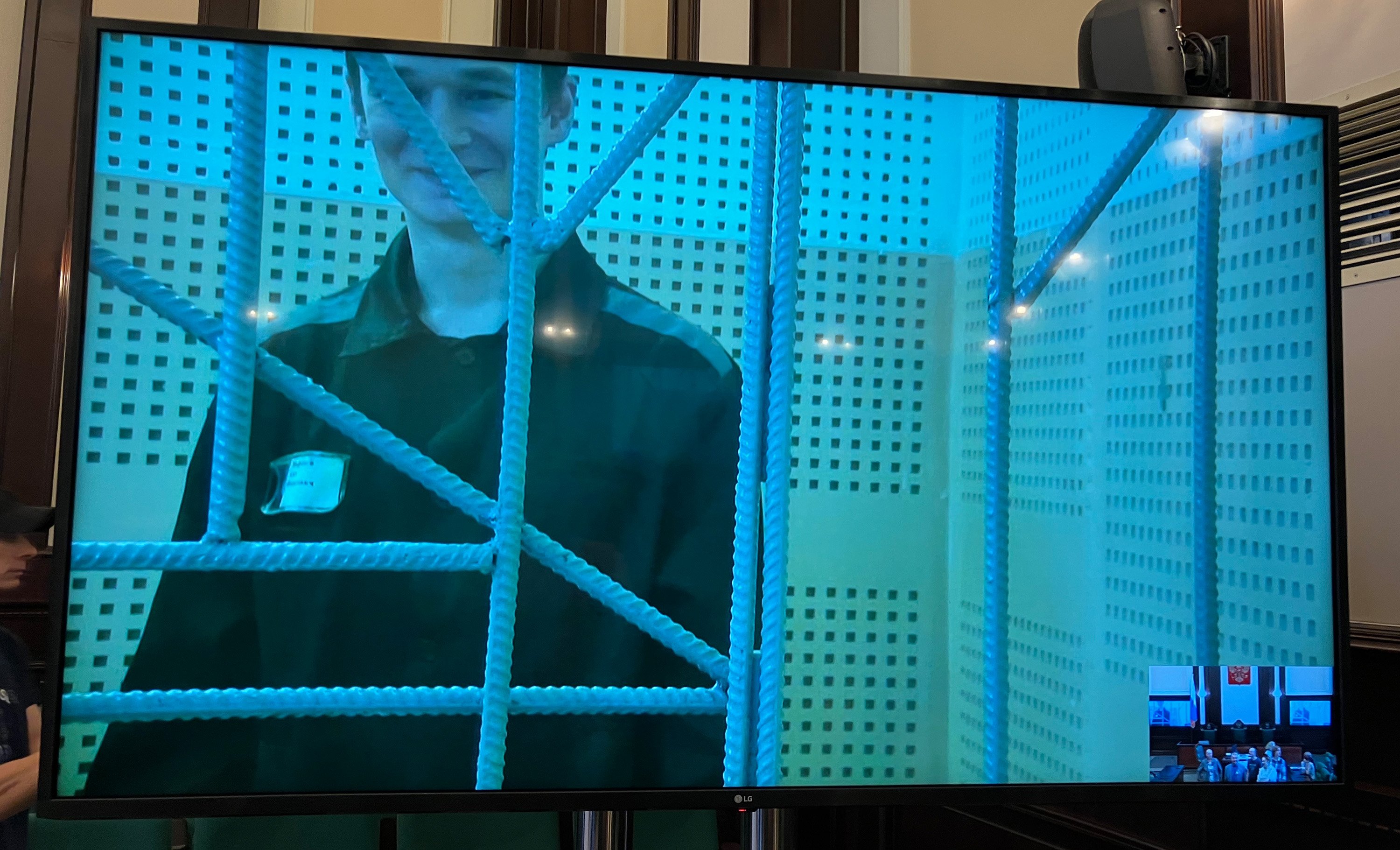

Photo: Mediazona

—

On the day he was due to be freed, Miftakhov was met at the prison gates by FSB agents who immediately re-arrested him. In a new trial based on his friend’s testimony, he was sentenced to another four years for “justifying terrorism.”

He is now held in a high-security prison in Dimitrovgrad, mostly in solitary confinement. His mental health has declined sharply. Trushkov, meanwhile, was released from the colony to fight for Wagner PMC in Ukraine. In a phone call to Miftakhov’s wife from the front, he slurred, “Get the kid out of there,” knowing Dimitrovgrad prison’s reputation.

Miftakhov is not scheduled for release until September 2027.

From Azat Miftakhov’s letter to Mediazona (abridged)

“There are no friends in prison,” as the inmates say. I don’t like such generalisations, but there is a certain amount of truth in it. Inmates are inherently placed in a vulnerable position. One wants to be released as soon as possible, another hopes for an unscheduled visit with his wife, and all of this depends on the goodwill of the administration. The administration knows the value of these benefits and sells them for special services. Snitching and betrayal are among them. And yes, prison status has no meaning here: “snitches” are found among both the “degraded” and “the men”. And you can’t say that the proportion among the former is noticeably different from the proportion among the latter.

Nevertheless, I managed to get burned by my friendship with Trushkov. Well, I have to admit that I am apparently a poor judge of character. This incident has significantly affected my perception of people in places of detention. When I meet a new person, I can’t help but start to assess whether he is capable of refusing the chekists if they try to force him to testify against me with threats and promises.

Editors: Maria Klimova, Anna Pavlova