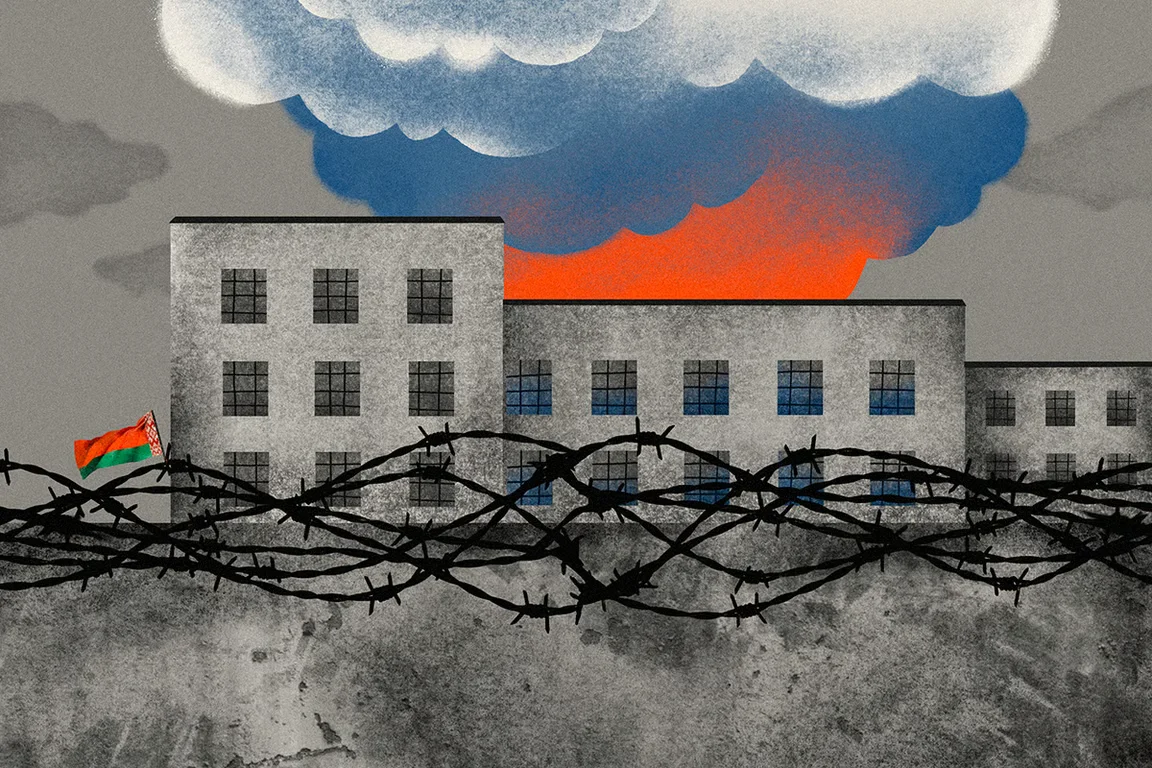

Special military obligation

How Belarusian political prisoners are being forced to support the Russian war effort in Ukraine

Illustration: Lyalya Bulanova

Despite Belarusian dictator Aleksander Lukashenko’s persistent denials, all evidence points to Minsk playing an active role in Russia’s war against Ukraine. Not only does Belarus permit Russian forces to use its hospitals and airfields, it also provides equipment essential for the Kremlin’s war machine, and the regime even forces its own prisoners to produce goods for the front.

After interviewing former political prisoners, Novaya Gazeta Europe has drawn up a list of military production sites in various prisons and penal colonies throughout Belarus where materiel is being produced for the Russian army.

Shell shock

Piatro* is a former prisoner who was sent to Penal Colony No.22, which is known by its inmates as the “Wolf’s Lair”, in Ivatsevichy, western Belarus, in 2021. Though his days were spent processing lumber before the war in Ukraine began, he recalls suddenly being forced to produce shell casings for the Russian Grad missile system while serving his sentence.

“In 2022, everything went sideways due to sanctions. Our bosses didn’t know how to react; they didn’t actually know how to lead, only how to command. The whole operation fell apart,” Piatro says. “We had two trucks loaded with timber that were left to rot, while orders started to come in for 3-meter-long crates, each loaded with two shells. Every day a truck would come to be loaded with 300 crates at a time.”

According to former inmates Novaya Europe spoke to, all six Belarusian “first-timer” prisons — colonies for prisoners with no prior convictions — were placed on a war footing following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and were reorientated towards the production of shell crates.

“I was just relieved that I was sent to the low-skilled metalworkshop, because in the lumber yard we would have had to build these crates and I’m not sure I could have. If you refuse to work, you are severely punished,” recalls Akihiro Hayevskyi-Hanada, who was a political prisoner at a penal colony in the city of Shklov, in eastern Belarus.

Beds, coffins and flowers

“When the grand funerals of ‘heroes of the Special Military Operation’ were shown on television, we noticed that they were our coffins, the ones we built,” recalls Maksim Viniarski, a former inmate at Penal Colony No.3. “I can’t say for certain, but the resemblance was uncanny.”

At the same time, in Penal Colony No.15, prisoners began to mass produce plastic memorial bouquets in staggering quantities, making all kinds of flowers from roses and carnations to cornflowers.

“It was simply impossible for Belarusians to be dying at such a rate for all of these flowers to be used,” one former inmate, Andrey Voynych, told Novaya Europe. “The usual quota was 500 flowers per worker per shift. We produced on average 3,000 to 6,000 flowers a day, which were taken away in trucks.”

By talking to his fellow inmates, Voynych realised that similar levels of production were taking place in other penal colonies as well. An anonymous businessman based in the city of Hrodna had signed contracts with several prisons and was exporting these mass-produced memorial bouquets to Russia non-stop.

At the start of 2023, in Penal Colony No.22, an urgent order was received for 500 beds. “When we had built a little over 400 of these beds, trucks came with packing crates and we had to quickly pack them and load them up,” he recalls, adding that on the boxes it said “produced at the request of the Defence Ministry of the Russian Federation in the Moscow region”.

Camouflage for sale

The standard activity of any Belarusian penal colony is garment production. Uniforms, gloves and special clothing for the Belarusian security forces are the most frequently produced items. However, after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Belarusian prisons began experiencing a new wave of orders.

“In late 2023, we received an order for camouflage, which we worked around the clock to fulfill — three shifts, six days a week,” says Akihiro Hayevskyi-Hanada. “The garment factory was made to work an hour later than people in the rest of the penal colony.”

Andrey Voynych, who served five years in Penal Colony No.15 in Mahilyow, remembers that the first order for camouflage coincided with Russia’s mobilisation in September 2022, while later orders coincided with major Russian offensives in Ukraine.

This order also clearly stood out, with prisoners working in sets of three shifts rather than the usual two to fulfill it. “You have to remember that the guards saw us as furniture, openly saying in our presence that this camouflage would be going to Russia,” says Voynych.

In Penal Colony No.3, in the northeastern Vitsyebsk region, prisoner Maxim Vinyarskyi witnessed a surge in orders for camouflage towards the end of 2023: “The garment factory began to work on a three-shift basis, but the prisoners — either deliberately or instinctively — worked poorly. Everyone understood that they weren’t making mopheads, gloves or workwear anymore. Three-shift-work carried on for three months in a row, but camouflage production at the site ultimately ceased due to quality concerns. The customer probably did not accept it.”

Vinyarskyi didn’t work in the garment factory himself — he made envelopes. But even something so innocuous turned out to be for use by the military. “In 2024 we got a huge, unexpected order. We had to produce 700,000 thick, dark brown envelopes made out of craft paper. They told us they would be used to send passports. I immediately thought to myself, hold on, where did 700,000 new Belarusian citizens come from?”

“We quickly put two and two together and realised that these envelopes were fit for three uses: sending call up papers, letters of condolence and for returning the passports of those who would no longer need them. I know for certain that they made these envelopes in other prisons as well … You can just imagine the scale of production.”

When the penal colony received major orders from the military, all the inmates who were assigned to work on the project were given uniforms and enlisted in the army’s internal support services. Alongside these orders also came militarisation.

Purple haze

In every Belarusian prison colony, there are always low-skilled workshops. These are primarily for metalwork, and are often populated with political prisoners.

“They bring old cables and wires to the workshop, from which we had to strip and extract the copper, aluminium and lead,” says Akihiro Hayevskyi-Hanada. “None of us saw any direct evidence, but we feared that the same lead was later used to make bullets.”

In Hayevskyi-Hanada’s penal colony, cables were brought in from the Homyel region and, he suspects, from the Chernobyl exclusion zone. "Occasionally, when we removed the wire jacket we found labels indicating that they were from 1980 or 1981. It was clear that they had survived the Chernobyl disaster.”

“We extracted tons of lead in Penal Colony No.3,” Vinyarskyi remembers. “The bosses came up with the idea that for a better yield, it ought to be smelted. Have you ever heard of open-cast lead smelting? It’s hard to think of anything more dangerous or harmful. We also burned building insulation, tar and other similar materials.”

The smoke over the colony was so thick that members of the local fire brigade, who were “furious” at what the prisoners were burning, had to be called, he says. “Black smoke hung over the city and it was impossible to hide where it was coming from. Only after the emergency services complained did we stop smelting lead.”

Meanwhile, prisoners at the Mahilyow colony were burning copper. “They did it in the old-fashioned way: burning plastic in the open air, without any filters and without any sort of protection,” one former prisoner recalls.

“Right next to the penal colony there was a rapeseed field towards which all of this vile smelling smoke wafted — sometimes black, sometimes yellow, sometimes orange and sometimes even purple.

“At least there was one thing to be happy about,” he says. “The prison guards were forced to breathe the same air as us.”

* Name changed for safety reasons