People Kidnapped and Sentenced with “Espionage” and “Treason” in Occupied Territories of Ukraine

People Kidnapped and Sentenced with “Espionage” and “Treason” in Occupied Territories of Ukraine

From July to September 2025, courts in Russia’s so-called new territories imposed sentences in this category of cases every three days. Teenagers, pensioners, women, and even entire families have fallen victim to the repression

Доступно на русскомDate13 Oct 2025AuthorsPolina Uzhvak, Sonya Savina, Rina Nikolaeva

In the three years since Russia formally annexed the so-called DPR, LPR, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson Oblasts, courts established by the occupying authorities have issued at least 190 sentences for “treason,” “espionage,” and “confidential cooperation with foreigners” to the civilians in these territories.

After examining the documents, we have learned that:

Sentences for “treason”, “espionage” and “confidential cooperation” are being imposed more and more often: from July to September 2025, they were issued once in every three days, meanwhile before the war Russian courts would issue no more than 16 such sentences per year.

The average sentence is 13.5 years in prison. There are at least two known cases of life imprisonment.

In the occupied territories, 28% of the sentenced on these charges are women. The average proportion in Russia would be 6%.

At least eight cases of sentenced teenagers are known

Kidnapped Ukrainian civilians are almost never exchanged: only one in 24 those exchanged is a civilian (the rest are military POWs).

At least five of the kidnapped have died in captivity.

At least 654 Ukrainian civilians have been prosecuted in the occupied territories or in Russia since the beginning of the full-scale war.

The actual figures are higher, as we were only able to examine the publicly available data.

Two thirds of the sentences have been imposed for “espionage”. This is a charge under which foreign citizens (in this case, Ukrainian passport holders) and stateless persons are tried in Russia. For a year, however, the number of “treason” convictions, which are used for Russian citizens, has been increasing (as residents of the so-called “new regions” are systematically forced “to get Russian citizenship: otherwise it is impossible to find a job or receive pension and medical care).

However, as human rights activists have told us, Ukrainians without Russian citizenship also get convicted of “treason”, even though it technically contradicts the legislation. Those with both Ukrainian and Russian passports are sometimes charged with both “espionage” and “treason”. As to the “confidential cooperation” charges, they can be legally applied to both Russians and foreigners in Russia.

Treason (Article 275 of the Russian Criminal Code, punishable by 12 to 20 years’ imprisonment or life imprisonment) and espionage (Article 276 of the Criminal Code, punishable by 10 to 20 years’ imprisonment) are considered "especially grave crimes" in Russia. Before the war, no more than 16 people per year would be convicted with these charges. In 2022, the Criminal Code was updated with Article 275.1 — “Confidential cooperation with a foreign state, international or foreign organization” (punishable by three to eight years in prison). From the beginning of the full-scale invasion to July 2025, courts in Russia and in the occupied territories have sentenced 774 people on these charges, according to Kirill Parubets, a data analyst.

Explaining our calculationsIStories compiled a list of those convicted with any of the three charges (Article 275, “Treason”; Article 275.1, “Confidential cooperation with a foreign state, international or foreign organization”; Article 276, “Espionage”) in four courts in the occupied territories of Ukraine (Zaporizhzhia Oblast Court, Kherson Oblast Court, Supreme Court of the Luhansk People's Republic, Supreme Court of the Donetsk People's Republic) from 2022 to 2025.

Only the Supreme Court of the Donetsk People's Republic publishes its sentencing records, so in addition to the court data, we used other sources: a list of political prisoners compiled by Memorial, a human rights organization; Kirill Parubets' list of individuals under prosecution under the three charges (as of December 2024); and the official press releases from the four courts as well as the Prosecutor General's Office.

The website of the First Court of Appeals contains information about the appeals filed by courts in the occupied territories against the verdicts on all three charges. Since it is impossible to compare the cases collected from open sources with the cases from the First Court of Appeals database, we took a cautious approach: we assumed that appeals might have been filed in all the publicly known cases and added the difference between the number of appeals and the publicly known cases for each court to the total number.

Our calculations only include cases that have been made public through human rights defenders, courts, or official reports. In reality, there are more similar cases and sentences, as some of them are never made public.

From “we didn't kidnap him” to being sentenced

The people sentenced for “espionage” and “treason” in the occupied territories are those who had been kidnapped months (and sometimes years) before the charges were filed. Kidnapping is one of the ways to suppress the residents who oppose the occupation. Since the very beginning of the war, people have been disappearing in the occupied territories. We have written about kidnappings in Kherson, Melitopol, and other occupied cities of Ukraine.

Iryna Horobtsova was kidnapped in May 2022, on her birthday. Soldiers came to her home in Kherson, where she was living with her parents during the occupation, searched the house, took her computer, phone, flash drives, and took Iryna herself, too. One of the soldiers told her parents that their daughter would return in the evening. Horobtsova has not returned home to this day.

For a long time, her parents did not know where their daughter was. “We are looking into it, so please wait,” they were initially told at the military commandant's office. Then they were advised to look for their daughter “in the Federal Security Service premises in Crimea.”

For more than two years, Horobtsova was held in a Crimean detention center with no contact with the outside world. The woman was banned from making phone calls, meeting relatives, receiving parcels, and even seeing her lawyer. The parents would receive the same response to their official requests to the Crimean FSB: “She will be detained until the end of the special military operation.”

In her entire time in prison, the parents have only been able to receive a few letters from her. "She wrote that she had been in the solitary confinement cell for the first three months, that she was doing exercise, that she was reading a lot of books. She was very worried about us. She asked us not to worry about her. Irina knows that Kherson has been liberated. She was looking forward to the liberation of the city so much, and so were we. And now we have been liberated, unlike her," said the father of the kidnapped woman.

From dozens of interviews with the families of the kidnapped and those who have returned, the same pattern emerges. The individuals were kidnapped by unidentified people who had not introduced themselves, had not shown any documents, and did not explain anything to their families. The person would simply disappear. At the military commandant's office, at the prosecutor's office, in the police or in the Investigative Committee - all the officials would say they “knew nothing” about their location. Sometimes the local police would even open a “missing person” case.

No one knew that there was a criminal case against Horobtsova until the spring of 2024. And In August 2024, 27 months after she had been kidnapped, the Kherson Oblast Court sentenced Irina to 10 and a half years in a general-regime colony on the "espionage" charges. “Over the course of a year, she collected the strategically important data on Russian Armed Forces units in the Kherson Oblast and passed it on to an employee of the Main Directorate of Intelligence of Ukraine,” the Prosecutor General's Office stated in a press release. From this statement one can judge that Horobtsova continued to gather information about the Russian Armed Forces while already in a detention center in Crimea.

"In almost all of the convicted individuals' cases, the explanations start with ‘we did not kidnap him’ or ‘they were detained for opposing the military operation’ and it all ends with a sentence. This is how the occupying authorities are attempting to legitimize the kidnappings of the previous years. Now they are digging up the cases of those who were kidnapped back in 2022-2023," says Alexei Ladukhin, a human rights activist with Every Human Being.

Grounds for prosecution: a 70-dollar transfer and chatting with family

“From December 2023 to May 2024, she made six transfers to the Ukrainian volunteers and military personnel via the Privat24 mobile app, for a total amount of 2,949.96 hryvnia, equivalent to 6,999.45 rubles [equivalent to approximately 70 dollars — IStories].”

This is a quote from a press release by the Zaporizhzhia Oblast occupation court. For this transfer, a woman from Energodar was sentenced to 14 years in prison under “treason” charges. The same sentence was imposed on a 73-year-old pensioner from the Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Oleksandr Markov, for transferring 15,500 hryvnia (about 370 dollars) “to the accounts of a foreign bank used by the Ukrainian intelligence.”

Court press releases are one of the few sources of information about those sentenced in the occupied territories. Cases of “treason” and “espionage” are usually tried in closed court hearings, and the names of those convicted are almost always hidden in the records. Details of the prosecution only become known if the relatives speak out.

The average sentence Ukrainians in the occupied territories get for “espionage” is 13 years and 3 months in prison (for “treason” it’s 13 years and 8 months). At least two cases of life sentences are known. The Zaporizhzhia Oblast Court gave these sentences to two people from Tokmak. In both their cases, according to the prosecutors, the men “gave the Ukrainian Armed Forces data on the location of Russian Armed Forces personnel and defenses,” which were then hit. Three Russian soldiers died in the first instance, and seven in the second.

Only one-tenth of all conviction reports involve any similar consequences of the “espionage” or “treason” Ukrainian civilians are charged on. In the rest of the cases, it only involves “the data that could have been used against the national security of the Russian Federation.”

In some cases, people are sentenced for sharing the things they had seen with relatives or friends — the court would consider this an evidence of cooperating with the Security Service of Ukraine or the Armed Forces of Ukraine. "People are often charged with treason and espionage for some completely trivial reasons. The prosecutors take a phone and find photos of the strikes, or some chats with relatives. This could be the grounds for a charge. One woman was charged with treason for telling her husband (in their private chat) that soldiers were stationed at a local civilian facility. These are such absurd charges of such a serious offence!" says Yevgeny Smirnov, a human rights activist with the Department One group.

Teenagers, mothers, entire families

Oleksandr Markov, the 73-year-old man who is the oldest of the convicted Ukrainian civilians, is one of those whose cases have been made public. The average age of those convicted of “espionage” and “treason” in the occupied territories is 39, although there are also teenagers and pensioners among the convicts.

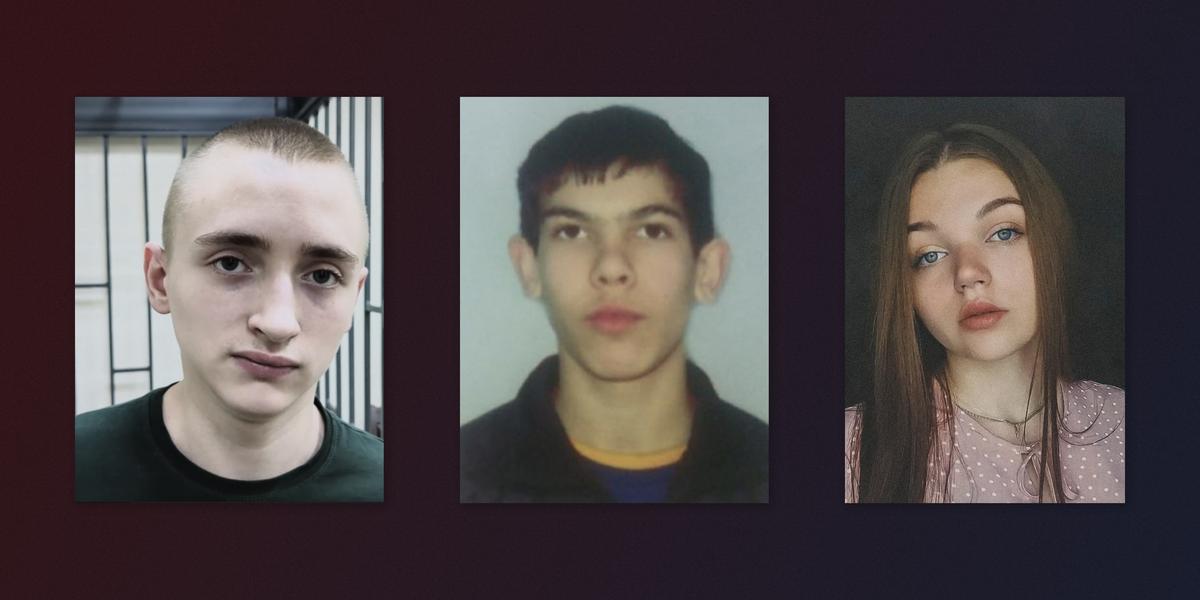

It has been publicly known about at least two sentenced minors' cases. Both were given real prison terms ranging from six and a half to nine years. The total number of convicted teenagers (young people up to 19 years of age, according to the UN definition) is now eight, including two girls. The most severe punishment was given to Mykyta Polozov from the occupied Donetsk Oblast, who was 19 at the time of sentencing. He got 13 and a half years in prison. Another teenager, 18-year-old Oleksandr Syrov from Mariupol, was sentenced on both charges at once — for “treason” and “espionage” (Syrov has both Ukrainian and Russian citizenship).

Artem Kudzhanov was detained by Russian security forces when he was 19, allegedly for collecting data on Russian military personnel in the Luhansk Oblast. In 2025, he was sentenced to 12 years in a strict regime penal colony. His father, Ibrahim Kudzhanov, was kidnapped from a hospital in 2024, tortured with electric shocks and then sentenced to five and a half years in prison, charged with “participation in a terrorist community” (Article 205.4).

Most often it is men who are tried for “treason,” “espionage,” and “confidential cooperation” in the occupied territories. However, more than a quarter of the sentences (28%) are imposed on women. This percentage is almost five times higher than the national average for women sentenced for the same charges. According to data from the Judicial Department of the Russian Supreme Court (which does not yet include statistics on the occupied territories), in 2024 only 6% of those convicted for “treason,” “espionage,” and “confidential cooperation” were women.

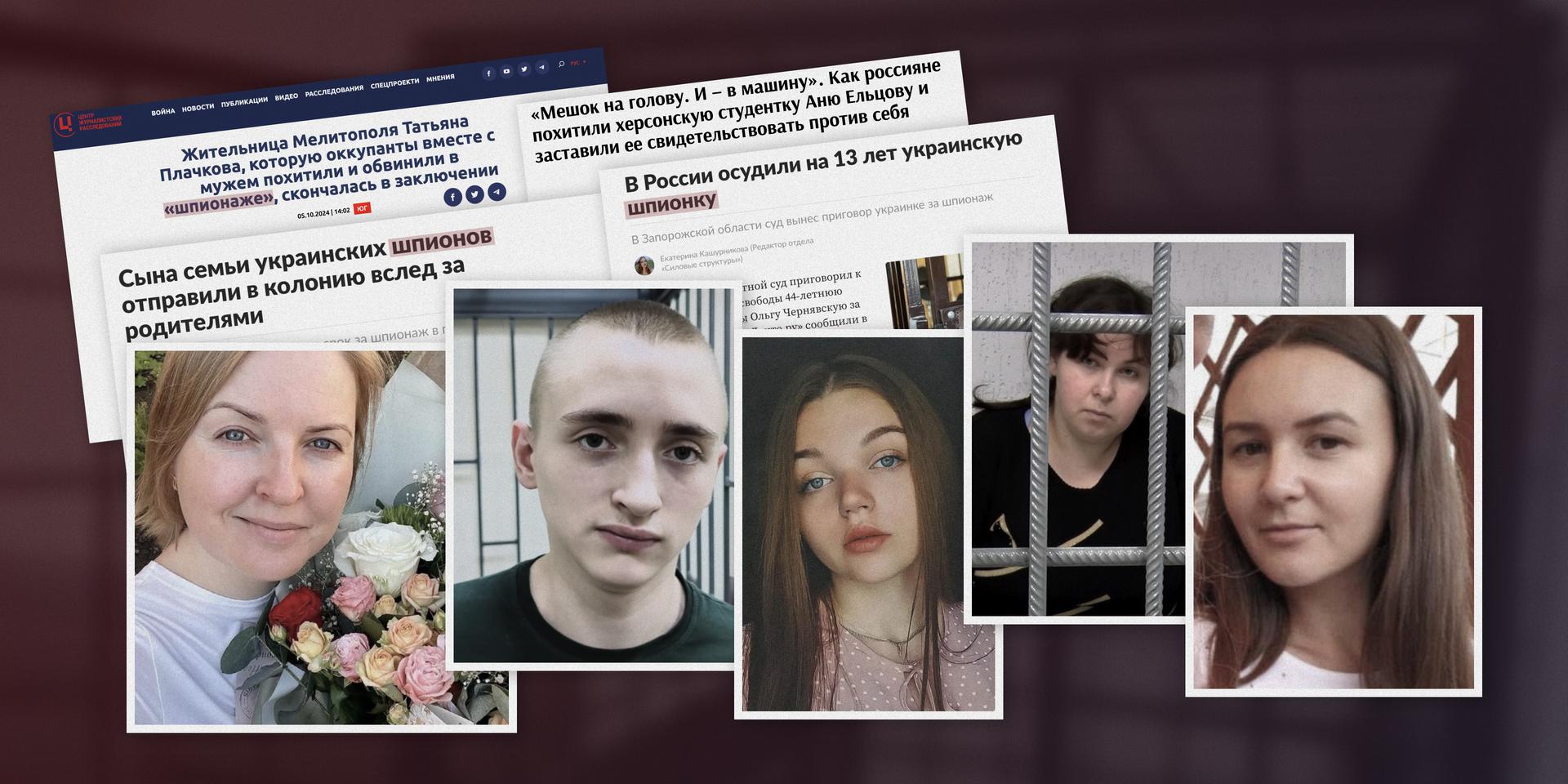

One of the convicted women is Anna Yeltsova from the Kherson Oblast. Russian security forces broke into her grandmother's house in the village of Ahaimany in November 2022 and kidnapped the 21-year-old student in front of her relatives. In February 2025, she was sentenced to 10 years in prison on the “espionage” charges. The Center for Investigative Journalism in Ukraine found out that it was the head of the village's occupation administration, Halyna Kostenko, who wrote a report on her. According to journalists, this was her way to take revenge on the student's family: Anna's grandmother, an Ahaimany school principal, had refused to cooperate with the occupiers.

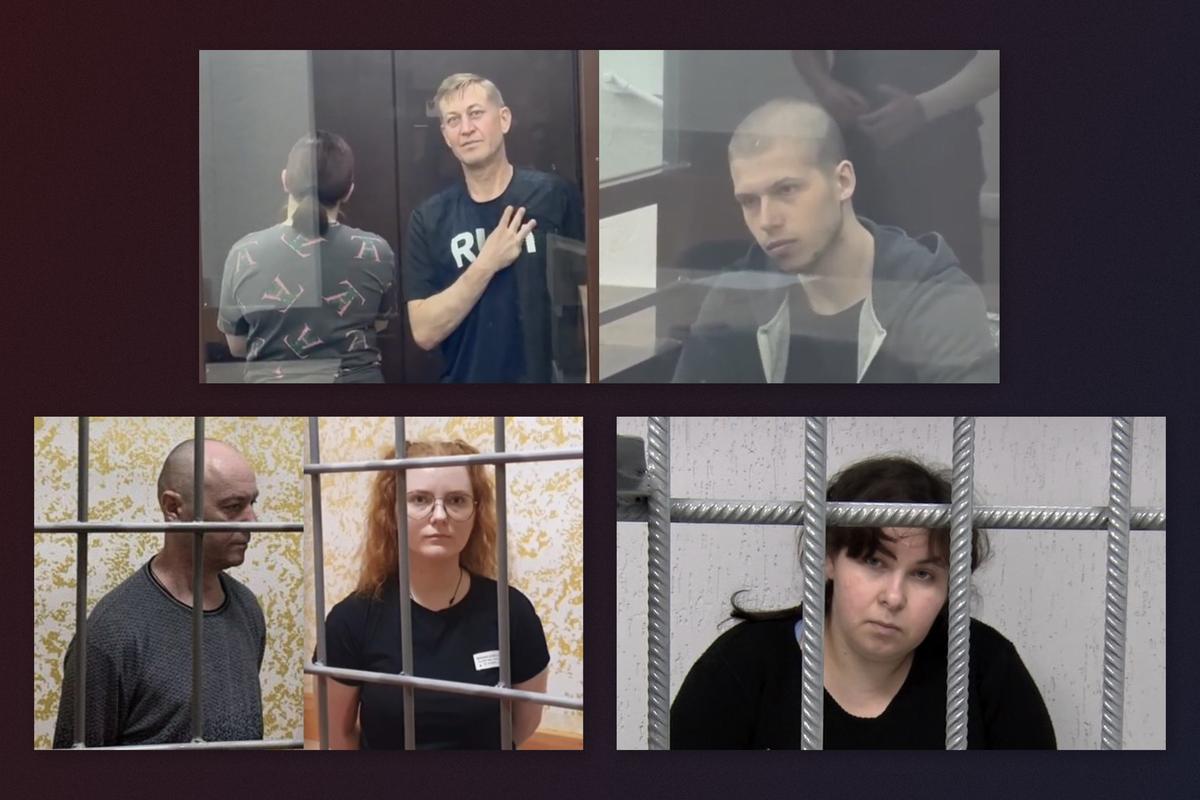

There are mothers (including those with many children) among the convicted women. For example, in the winter of 2025, 32-year-old Olena Danilenko from the village of Demyanovka in the Kherson Oblast was sentenced to 12 and a half years in prison. Olena has four underage children, and the youngest is five years old. She was charged with "treason". According to the prosecutors, the woman collected data on the Russian military equipment and troops movement and passed it on to the Ukrainian intelligence. Her brother, 24-year-old Oleh Rashchupkin, was sentenced to 12 years in prison under the charges of "espionage", stating the same reasons.

This is not the only case in which multiple members of a family are convicted of “spying”. Two similar cases happened in Kherson Oblast. In one, a father and a daughter were convicted. In another, it happened to two brothers who, according to the prosecutors, gave the information about the Russian militaries to their third brother, who served in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. In Luhansk Oblast, an entire family, the Ryzhkovs, were sentenced to prison for “espionage”: a 20-year-old man and both his parents.

Deaths in captivity

Oleksandr Markov, the pensioner sentenced to 14 years for a bank transfer, died in June 2025 while being transferred to the Krasnodar Oblast. The man, ill and elderly, was arrested on May 8, 2024. For nearly a year, until March 2025, his family knew nothing about his fate.

Markov is not the only one who died. The lists of prosecuted Ukrainians kept by Memorial include five people who were kidnapped after the start of the war and are now listed as dead. Four of them were kidnapped in the occupied territories.

Among them is Tetiana Plachkova from Melitopol, who had been charged with “espionage.” Russian security forces detained her and her husband Oleh on the night of September 25 to 26, 2023. For almost six months, their daughter Lyudmyla did not know where her parents were.

In February 2024, the girl was informed that her mother was in a coma in a Melitopol hospital. Lyudmyla asked the FSB to allow Tetiana to be transferred to a medical facility in territory controlled by the Ukrainian government. But she did not receive a response. Eight months after her kidnapping, in May 2024, Tetiana Plachkova died. The death certificate stated that she had pneumonia and lungs and brain edema. It remains unknown where her husband is.

The actual number of deaths may be much higher. Kidnapped residents of the occupied territories are kept for a long time in the unofficial detention facilities, known as “basements,” without being formally charged. People are held in harsh conditions and subjected to torture, which is what some don't survive. If a person dies there, their death is usually not recorded in any way, says Yevgeny Smirnov, a human rights activist with the Department One.

In Melitopol and its district alone, there are at least three known cases of deaths among those who had been kidnapped, a representative of Kidnapped Melitopol Residents, a Ukrainian authorities local council project, told us.

Ukrainian journalist Viktoriia Roshchina is among those who died in Russian captivity. In the summer of 2023, she went to the occupied territories to find places where kidnapped Ukrainians were being held, and disappeared herself. A year and a half later, her body was returned to Ukraine with signs of torture. IStories investigated the circumstances of her kidnapping and death.

The number of people kidnapped is many times higher than the number of criminal cases

The 190 people convicted of “espionage,” “treason,” and “confidential cooperation” by courts in the four occupied regions whom we were able to identify are only a small fraction of the Ukrainians prosecuted in the occupied territories.

Some civilians are tried under other charges, such as “organizing a terrorist community” or “participating” in it. Such cases are often tried in the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don. The cases of many kidnappees are heard in Russian or Crimean courts.

In total, Memorial's database contains information on 654 Ukrainian civilians who have been prosecuted in the occupied territories or on Russian territory since the start of the full-scale war. With 355 of them, the prosecution began in the regions occupied after 2022, and 66 of them have not yet been charged (we do not have the accurate information about the citizenship of all the residents of the occupied territories, but we count them all as Ukrainians).

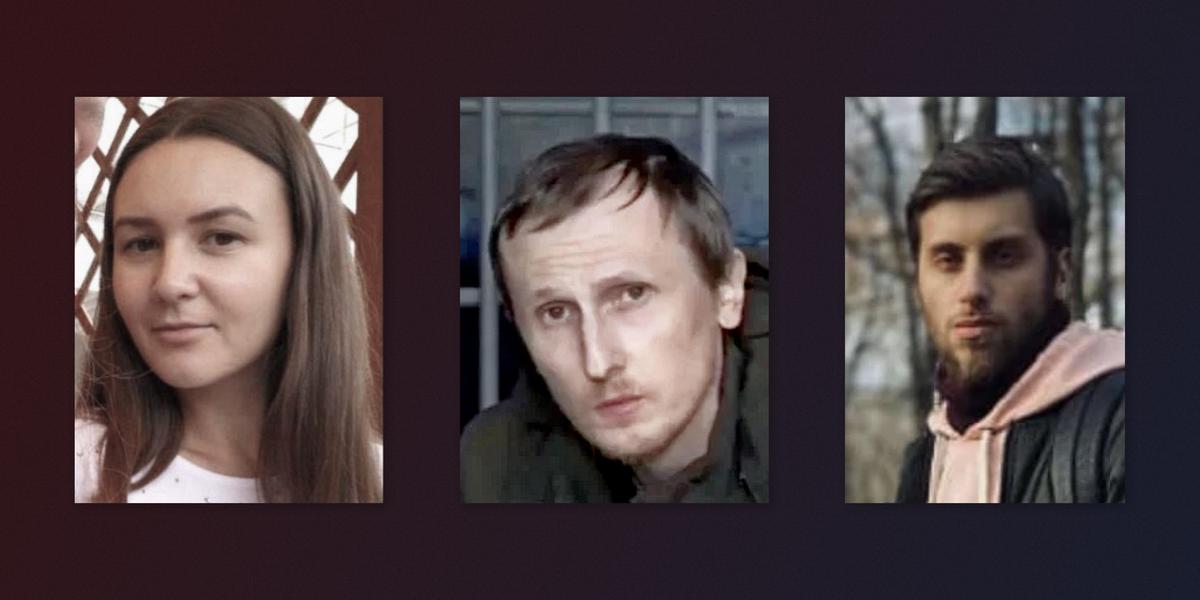

Among them is a Melitopol journalist Anastasia Hlukhovska, who was kidnapped from her home in August 2023. For more than two years, her sister and mother have been learning about her state from the fragments of information from those of her cellmates who managed to get out. At first, the girl was held in an industrial zone territory in Melitopol, then she was transferred to a pre-trial detention center in Taganrog, and later to a pre-trial detention center in Kizel, Perm Krai. She still has not been charged with any offence.

Along with Hlukhovska, there are other journalists who were also kidnapped. Only two of them have reached the trial stage. Heorhiy Levchenko, administrator of the “RIA Melitopol” Telegram channel, was sentenced to 16 years in prison for “treason” by the Zaporizhzhia Oblast Court, while Oleksandr Hershon, administrator of the “Melitopol is Ukraine” Telegram channel was tried in Rostov-on-Don. He got 15 years in prison for “espionage,” “participation in a terrorist community,” and “committing a terrorist act.”

Since the beginning of the war, 358 people have been kidnapped in Melitopol and the district alone, 11 of them in the last six months, a representative of the Kidnapped Melitopol Residents project told us. 144 people are still in captivity, and only 31 of them have been brought to trial. Many of the kidnapped, like Anastasia Hlukhovska, are held incommunicado — with no contact with the outside world.

Ukrainian human rights activists estimate the total number of people kidnapped in the occupied territories to be 7,000 to 16,000. According to the Office of the Ombudsman of Ukraine, it is confirmed that 1,800 of them are being held in Russia. According to Mikhail Savva, an expert with the Center for Civil Liberties, the imprecision of the estimate is due to Russia's refusal to provide information about people kidnapped and to allow international organisations access to them. The kidnappees have no communication or access to lawyers, and they cannot say where they are or what is happening to them.

Kidnapped Ukrainian civilians are almost never exchanged: only one in 24 of those exchanged is a civilian

"Mom, I'm alive, I'm being tried on the charges of Article 276. Only an exchange can save me. Take care of yourself." These were the first words that Kostyantyn Maksymov was able to pass on to his mother a year after his kidnapping. Maksymov is a priest of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church from the occupied town of Tokmak in the Zaporizhzhia Oblast. He refused to sign documents to transfer to the Russian Orthodox Church and to mention Russian Patriarch Kirill during church services. Due to the constant pressure, he attempted to leave the occupied territory in May 2023, but was detained during the "filtration" process. He would be held in "basements" in Melitopol for about a year. Maximov's mother said that he was tortured. A year later, he was sentenced to 14 years’ sentence under the espionage charges.

Sentences for “espionage,” “treason,” and other politically motivated charges are what might await thousands of civilian hostages. And while Ukrainian soldiers captured by the Russians have a chance of returning home during an exchange, civilians have little hope. They have only been exchanged in exceptional cases.

A source among Russian lawyers familiar with the exchange process called it “a completely opaque and very unfair instrument”.

Since the beginning of the full-scale war, Ukraine has returned 6,235 Ukrainians, said Dmytro Lubinets, the Ukrainian Parliament's Commissioner for Human Rights. Only 372 of the returned are civilians. Among these civilians are the 120 prisoners who had been detained in the territory of Ukraine before the war began, were then taken to Russia and would be subject to deportation in any case, Mikhail Savva, an expert at the Center for Civil Liberties, told IStories. These people were handed over to Ukraine in May 2025 as part of a large “1,000 for 1,000” exchange. Unless they are included in the exchange statistics, it turns out that only one in 24 of those exchanged is a civilian. Ukrainian human rights organisations, as well as Russian human rights advocates, are now trying to make the release of all prisoners of war a priority in the negotiations.

The last time Ukrainian civilians were returned was during the exchange on October 4; 20 civilians were returned, but little is known about who they are. Prior to that, eight kidnapped civilians were returned from captivity on August 24. Among them were Mark Kaliush, who had been subjected to forced psychological treatment in Russia; UNIAN correspondent Dmytro Khilyuk, who was kidnapped from the Kyiv Oblast at the very beginning of the invasion; and former Kherson mayor Volodymyr Mykolayenko, who refused to cooperate with the occupying authorities.